Before diving into today’s topic on how President Trump’s policies are undermining trust in the US as a credible borrower, let me start with some good news—especially for those who understand Danish. My new book, How Low Interest Rates Change the World, will soon be published in Danish! Even better, the Danish version will be priced far more accessibly—likely just 25–30% of the price of the global version. And there’s more: I’ll be adding a couple of new chapters exploring the similarities and differences between developments in Denmark and the global trends discussed in the book. The Danish version is set for release this autumn (October). In the meantime, you can check out some of the broad coverage the book has already received in the Danish media: Berlingske, Borsen, Finans/JP, Politiken.

Abstract of today’s analysis:

Following US President Trump’s ill-judged tariff announcement on 2 April, clear signs have emerged that investor confidence in the United States is beginning to erode. While President Trump claimed that ‘people were getting a little yippy,’ the reality points to a far more significant development: an emerging erosion of trust in the US as a credible borrower. This loss of confidence could prove costly for the US in the long term.

On 9 April—just one week after imposing sweeping tariffs on all US trading partners during the calamitous ‘Ruination Day’ of 2 April (link)—Trump was forced to backtrack. He announced a 90-day pause on the tariffs, stating that people were ‘getting a little bit yippy, a little bit afraid’ (link).

This, frankly, is an extraordinary understatement. In this post, I want to explain just how severely trust in the United States was eroded in such a short space of time—and why this breakdown in confidence is so unusual.

Credit Default Swaps (CDS)

The United States has amassed a significant amount of debt.

If you’re a lender concerned that the borrower might fail to repay, you can purchase insurance to protect yourself against that risk. In the financial world, this insurance is known as a Credit Default Swap (CDS).

CDS exist for a wide range of credit instruments. In this context, we’re focusing on confidence in the United States as a sovereign borrower—that is, CDS on US Treasury securities.

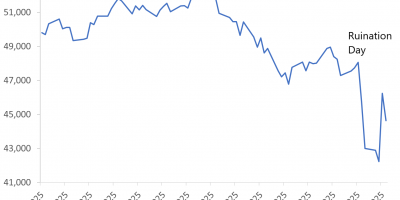

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the 5-year CDS premium on US government debt over the past decade. The CDS premium, measured in basis points, is the cost you pay to the seller of the insurance (the CDS issuer) for protection against a US default at some point over the next five years.

For example, if you hold $10 million in US Treasuries and the CDS premium is 50 basis points, you would pay $50,000 annually to the insurer. In return, the insurer would cover your losses if the US government were to default over the next five years. The greater the perceived risk of default, the higher the premium. As such, movements in CDS premiums serve as an indicator of changing perceptions regarding the likelihood of a US default.

Figure 1. US 5-year CDS premium. Daily data. 1 January 2015 – 24 April 2025. Source: Datastream via LSEG and J. Rangvid.

In Figure 1, two clear spikes in CDS premiums on US Treasuries stand out: one in May 2023 and another following ‘Ruination Day’.

The spike in May 2023 was triggered by the US debt ceiling crisis (link). As you may recall, that year was marked by intense political wrangling over whether to raise the debt ceiling. Had the ceiling not been raised, the US government would have lacked the funds to meet its obligations—including payments to its creditors. As the deadline approached, fears of a potential default grew, prompting a sharp rise in CDS premiums.

(A quick aside: we are once again nearing the debt ceiling, and a new round of political brinkmanship may be on the horizon. According to the Congressional Budget Office, ‘if the debt limit remains unchanged, the government’s ability to borrow using extraordinary measures will probably be exhausted in August or September 2025’ (link). A renewed debt ceiling standoff, layered on top of the current turbulence, could further undermine confidence in US creditworthiness.)

The second spike in CDS premiums, also visible in Figure 1, was caused by ‘Ruination Day’. You can see how rapidly the premium climbed—from 37 basis points before 2 April to 52 basis points today. This was not simply markets “getting a little yippy”; it reflected a serious and swift erosion of trust in the United States’ financial credibility.

CDS premiums: Different countries

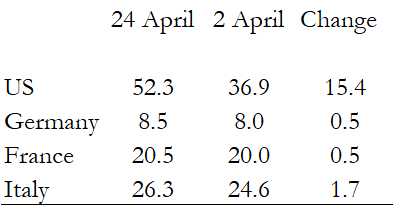

Another way to observe the loss of investor confidence is by comparing the movements in US CDS premiums to those of other major economies. Table 1 presents the changes in CDS premiums for US sovereign debt alongside those for French, German, and Italian debt since ‘Ruination Day’.

Table 1. US, France, Germany, and Italy 5-year CDS premium. April 2 and 24 April 2025. Source: Datastream via LSEG and J. Rangvid.

There has been virtually no change in the cost of insuring against a default by France, Germany, or even Italy since early April—CDS premiums for those countries have remained broadly stable. In stark contrast, the cost of insuring against a US default has surged. It is now twice as expensive to insure US debt as it is to insure Italian debt.

This is striking, given that Italy is more indebted than the US: Italian public debt stands at around 135% of GDP, compared to 121% in the US (link). This disparity highlights just how damaging Trump’s erratic policy decisions have been to global confidence in the US as a reliable borrower.

The US dollar

The erosion of trust in US economic policy can also be seen in the behaviour of the US dollar.

The dollar is traditionally viewed as a safe-haven currency. In times of global uncertainty, investors tend to sell off non-US assets and buy US assets—especially US Treasuries—because they regard the United States as a more stable and secure place to park capital.

This trading behaviour normally strengthens the dollar in times of crises. When investors buy US Treasuries, demand for them increases, pushing up their prices and pushing down yields. And since foreign investors must first acquire US dollars to purchase Treasuries, this also increases demand for the dollar, causing it to appreciate.

Consider the euro–dollar exchange rate. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between the yield spread on 10-year US Treasuries over 10-year German bunds, and the USD/euro exchange rate.

Figure 2. Spread between yields on US 10-year Treasuries and German 10-year bunds together with the dollar-euro exchange rate. The exchange rate refers to the right-hand-scale, which is inverted. Period since ‘Ruination Day’ encircled. Daily data. 1 January 2024 – 24 April 2025. Source: Datastream via LSEG and J. Rangvid.

Figure 2 shows that, under normal circumstances, the yield spread between US and German government bonds tends to move in tandem with the dollar–euro exchange rate. When US yields rise relative to German yields, US assets become more attractive, prompting investors to buy dollars in order to purchase Treasuries. This increased demand typically strengthens the dollar. The reverse is also true: when US yields fall relative to German yields, the dollar tends to weaken.

But look at the far right of the figure. After ‘Ruination Day’, this relationship broke down. Despite significant market turmoil—stocks plunging and widespread investor panic—US yields rose sharply relative to German yields, with the spread widening by nearly 50 basis points. Yet instead of strengthening, the dollar weakened significantly.

There is only one convincing explanation: investors lost faith in the United States’ creditworthiness. Rather than seeking safety in US Treasuries and driving up demand for the dollar, they did the opposite—they sold Treasuries and moved their money elsewhere. This capital flight required converting dollars into other currencies, such as the euro, which put further downward pressure on the dollar.

Rising term premium

Trump has repeatedly stated that he believes the dollar is too strong, and he might welcome its recent decline. But he should not. The dollar’s weakening is not a reflection of strength elsewhere—it’s a signal of deteriorating trust in the United States.

This loss of confidence has serious consequences. When trust in a country’s financial stability erodes, investors demand a higher risk premium to hold its debt. For the United States—with its vast refinancing needs and unsustainable debt trajectory—this means higher borrowing costs.

As I’ve already shown, the cost of insuring against a US default has risen (Figure 1), and US yields have increased far more than German yields since ‘Ruination Day’ (Figure 2). The final piece of evidence is in Figure 3, which presents an estimate of the rising risk premium embedded in US Treasuries.

Figure 3. Term premium on US Treasuries. Period since ‘Ruination Day’ encircled. Daily data. 1 July 2024 – 24 April 2025. Source: Datastream via LSEG and J. Rangvid.

The risk premium represents the additional compensation that investors demand for holding US Treasuries, above and beyond the expected path of future short-term interest rates. Unlike yields, the risk premium is not directly observable—it must be estimated.

In Figure 3, I present the ACM (Adrian, Crump, and Moench) estimates of the term premium, as published by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (link).

As the figure shows, the risk premium on US Treasuries has been steadily rising since the autumn of last year—roughly the point at which it became increasingly likely that Trump would return to the presidency. More strikingly, there has been a sharp spike in the premium following ‘Ruination Day’. This reflects mounting anxiety among investors about what lies ahead with Trump back in the Oval Office, and growing doubts about the United States’ credibility as a borrower.

Conclusion

Trump reversed course on his aggressive tariff policy just one week after announcing it, claiming that people were getting “a little yippy.” This is a gross understatement. Investors weren’t just jittery—they were deeply alarmed.

We now see a range of indicators pointing to a loss of confidence in the United States as a borrower. I’m not suggesting that markets suddenly believe the US is fundamentally untrustworthy. Far from it. But the signs of doubt are unmistakable—and that shift matters.

The US has long been considered the world’s financial safe haven. That reputation is now being called into question. With an enormous debt burden to refinance and a fiscal outlook that is increasingly unsustainable, the country needs investor confidence. Trump’s policies have begun to erode that trust.

This is not just a political concern—it is a financial risk. And a dangerous one at that.