Based on IMF forecasts, I calculate the global cost of the crisis as foregone (because of the pandemic) global economic activity up until 2024. The cost amounts to USD 23,600bn, a quarter of global output in 2019. The cumulative output loss is almost twice as large in developing and emerging economies as in advanced economies, though China is an outlier. The calculation represents a lower bound on the final cost, as economic activity might not recover until 2024. Also, the calculation does not include health-induced costs, the inclusion of which would further increase the cost.

As the final (at least for the time being) part of my analyses of the cost of the crisis (link and link), I present here my calculation of the global cost of the crisis.

I calculate the global cost of the crisis as the cumulative loss of global economic activity due to the crisis. This crisis is a health-induced crisis, though. In my previous posts, I calculated both the loss of economic activity and health-induced costs for Denmark. I am not aware of methods to estimate the size of health-induced costs on a global level. Hence, I restrict this analysis to the loss of global economic activity, but discuss health-induced costs.

Expected growth rates

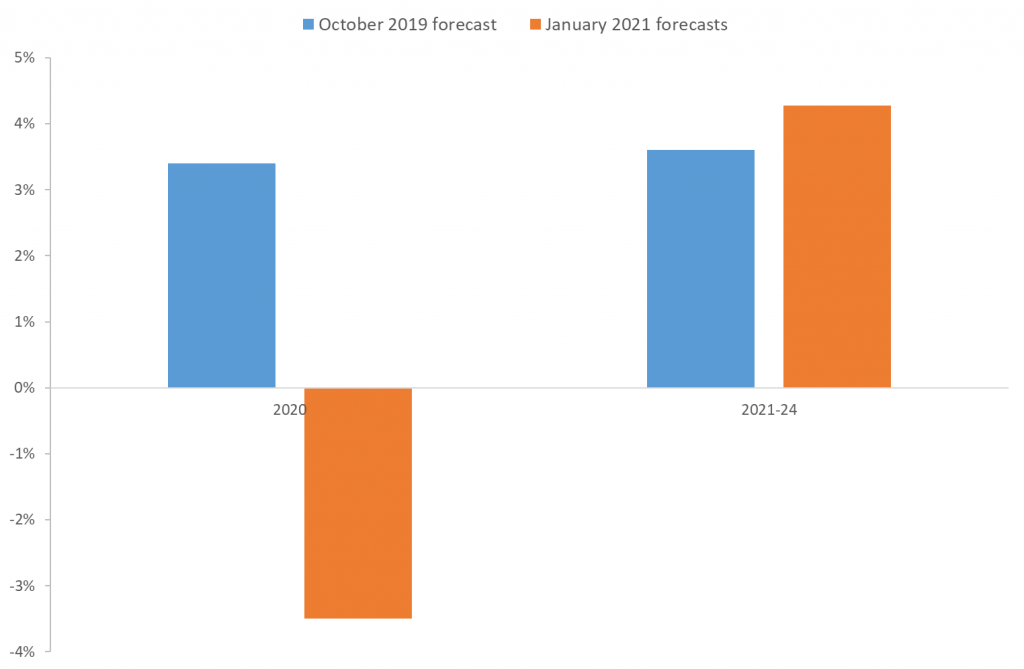

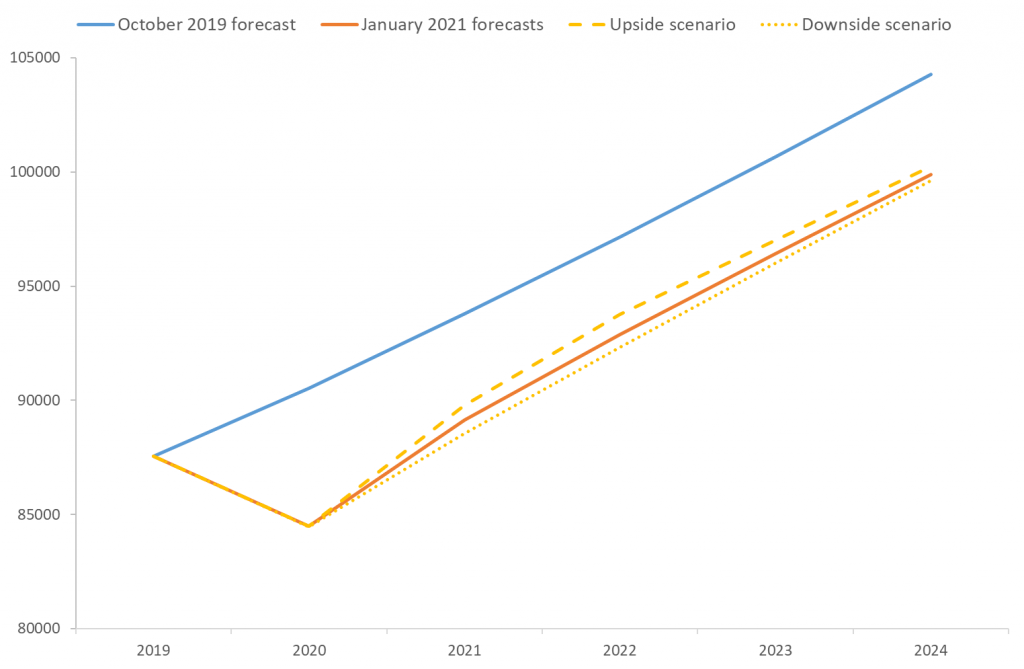

I base my calculations on IMF forecasts for global economic activity. I take IMF’s forecasts from October 2019, when nobody expected the arrival of the pandemic, and compare them to the recent January 2021 IMF forecasts for global economic activity. Figure 1 summarizes IMF’s expectations:

Source: IMF WEOs.

In October 2019, IMF expected global output to increase by 3.4% in real terms during 2020. There was no talk about a pandemic. Instead, the major risk mentioned was the uncertainty surrounding global trade and geopolitics (Trump and China).

2020 turned out to be so different. In their recent January 2021 WEO update, IMF now expects global output to contract by 3.5% in 2020. This means that the forecast error (= expectation in October 2019 – realized growth in 2020) amounts to 7%-point.

The pandemic and the resulting lockdowns caused this unprecedented recession. As a comparison, global output contracted by 0.1% “only” because of the financial crisis in 2009. In 2020, as mentioned, the contraction amounts to 3.5%. Globally, this recession has been so much more severe than the one following the financial crisis in 2009.

We do not have the final figures for 2020 yet. The 3.5% contraction for 2020 is a very good guess, though, given that we have the figures for the first three quarters of 2020 and higher frequency indicators for the last quarter, such as industrial production etc. Hence, I would be surprised if the final figure for 2020 turns out to be much different from this number, i.e. from a 3.5% reduction in global output.

Figure 1 also shows that global growth expectations for 2021-2024 have been revised upwards, compared to what was expected before the pandemic. In October 2019, IMF expected global output to increase by 3.6% per year on average during 2021-24. In January 2021, IMF expects the world economy to grow by 4.2% per annum during 2021-24. So, 2020 was worse than expected before the pandemic but 2021-24 is expected to be better. What do the revisions imply for the expected cumulative loss of economic activity during the 2020-2024 period?

The global loss of economic activity

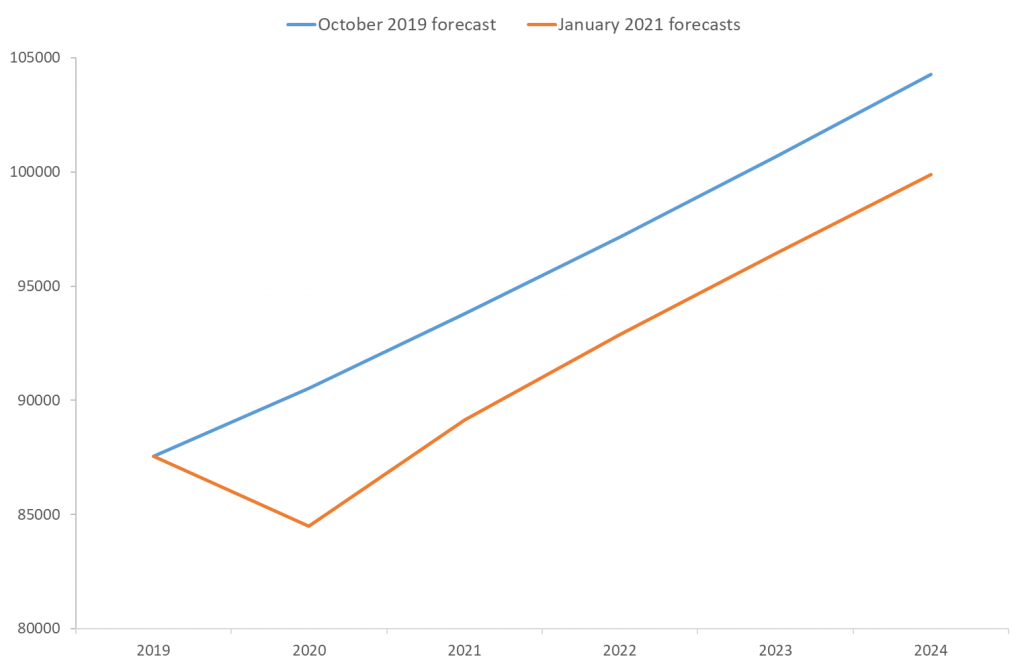

Before the pandemic, in 2019, aggregate global output amounted to app. USD 87,500bn. In this figure, I calculate the path of global output expected before the pandemic (using growth rate expectations from October 2019) and contrast it with the path expected now, i.e. taking into account the actual 2020 development and current (January 2021) forecasts for global growth during 2021-24:

Source: IMF WEOs and own calculations

In October 2019, the expectation was that global output would amount to app. USD 90,500bn in 2020 (in real terms). Instead, global output amounts to app. USD 84,500bn in 2020. In 2020, the world earned app. USD 6,000bn less because of the pandemic.

Figure 2 reveals that global output will most likely remain below the level expected before the pandemic during the next couple of years, in spite of the increase in expected growth over the next four years that Figure 1 illustrated.

In aggregate, during the 2020-2024 period, the difference between what was expected before the pandemic and what was realized in 2020 plus what is expected going forward from here amounts to USD 23,600bn. This is my estimate of the global cost of the pandemic. It is the value of foregone economic activity in 2020 plus the expected value of foregone economic activity up until 2024.

USD 23,600bn is a big number. To illustrate, it is 27% of 2019 global output. A quarter of one year’s global output has been lost due to the pandemic. It also (more or less) corresponds to the value of everything that is produced (GDP) in the still-largest economy in the world, the US, during one year. Or, more or less, one and a half times everything produced in China in a year. As a final illustration, it is app. 12 times Biden’s new stimulus package of USD 1,900bn.

Advanced vs. Developing and Emerging economies

The pandemic is global. The cost of the pandemic will not be shared equally among Advanced and Developing/Emerging economies, though.

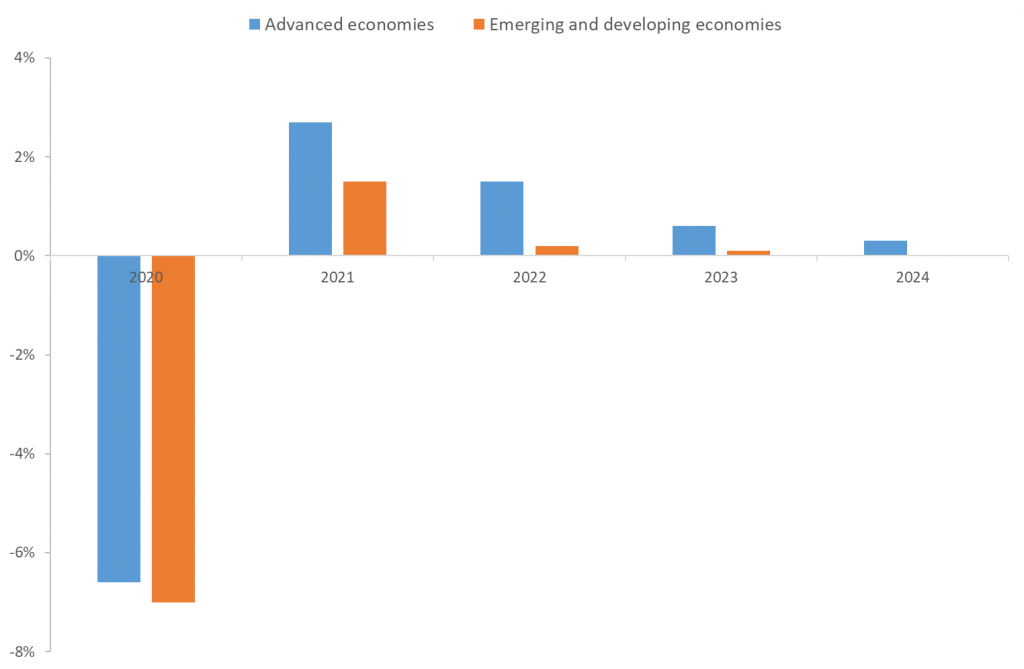

This figure shows that the forecast error for 2020, i.e. the difference between expected 2020 growth and actual 2020 growth, was equally large for Advanced and Developing/Emerging economies. For both Advanced and Developing/Emerging economies, growth during 2020 turned out to be 6%-7%-points lower than expected before the pandemic:

Source: IMF WEOs.

Advanced economies have provided substantial fiscal and monetary support to households and firms in 2020, as described elsewhere on this blog, helping to contain the contraction. Also, vaccines are expected to be widely available in Advanced economies during 2021, supporting the recovery as of summer 2021.

In contrast, it will take longer for vaccines to be rolled out in Developing/Emerging economies. Also, oil exporting and tourism-dependent Developing/Emerging economies have suffered particularly much, IMF mentions.

China differs from most other Developing/Emerging economies, as China has been successful in containing the pandemic after the initial outbreak in early 2020. Also, China has provided substantial fiscal and monetary support.

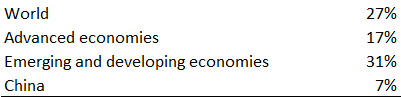

In total, this means that the cost of the pandemic will not be shared equally around the world. The output loss due to the pandemic will be 17% of 2019 GDP for Advanced economies, but will be almost twice as large, 31%, in Developing and Emerging economies. In Chinas, it will only be 7%:

Source: IMF WEOs and own calculations.

Uncertainty

There is considerable uncertainty surrounding the recovery. Will vaccines be rolled out according to plan, will we face new mutations that vaccines do not protect against, will consumers increase spending as much as we expect when restrictions as removed, etc.?

IMF presents up- and a downside forecasts that reflect this uncertainty. The calculations above are reasonably robust to the future risk scenarios. The reason is that the cost is mainly due to the contraction in 2020, and there is little uncertainty surrounding that by now.

Figure 4 presents the path of world output as expected before the pandemic and how it is expected to develop as of now, including up- and down-side scenarios:

Source: IMF WEOs and own calculations.

The magnitude of the cost of the crisis is not much affected by this uncertainty. The cost of the crisis is reduced to 24% (from 27%) of 2019 global output in the positive scenario but increases to 29% of 2019 global output in the downside scenario.

Health-induced costs

This analysis calculates the cost of the crisis in terms of foregone output around the world. The crisis is a health-induced crisis, though. In my previous posts that estimated the costs of the crisis in Denmark , I factored in the economic value of the costs of premature mortality, health impairments, and mental health impairments.

A similar global calculation requires estimates of the value of a global statistical life, as well as estimates of the number of people experiencing severe health impairments because of the virus, as well as the number of people facing mental health impairments. I know of no good way to calculate these such on a global level. Hence, in this post, I calculate the part of the cost due to foregone economic activity. This is certainly an important number to know in itself.

To give one perspective on the health-induced costs, though, Cutler & Summers (link) estimate that the economic value of health-induced costs in the US is, largely, equal to the loss of economic activity for the US. They estimate the total US loss at USD 17 trillion and the loss of economic activity in the US to USD 7.5 trillion, i.e. the loss of US economic activity corresponds to app. 50% of the total US loss. I estimate that health-induced costs are significant for Denmark, too (link and link), but relatively smaller than those calculated by Cutler & Summers for the US.

Conclusion

The global recession caused by the pandemic has been unprecedented in terms of both its magnitude, its cause, as well as the policy response. Based on IMF forecasts for global economic activity up until 2024, I calculate the global cost of the crisis in terms of foregone economic activity around the world. The global cost of the crisis amounts to app. USD 23,600 bn. It is an unfathomable number. It is the value of the reduction in cumulative global output resulting from the crisis. It is income that would have been generated around the world was it not for the pandemic. It corresponds to a quarter of total economic output in 2019.

As I do not have good estimates of global health-induced costs, I restrict the analysis to foregone economic activity. On the one hand, this means that the analysis is not an estimation of the total cost of the crisis (loss of economic activity + health-induced costs). On the other hand, it is certainly important to know the value of the loss of economic activity in itself.

I base my calculation on IMF data. In October 2019, IMF presented forecasts up until 2024. Hence, my calculations run until 2024. As shown in some of the figures above, global economic activity will in 2024 most likely not have reached the level expected before the crisis. Hence, the eventual global cost of the crisis might end out being higher than the number presented in this analysis.