The Danish parliament recently decided to raise the retirement age in Denmark to 70, effective from 2040. This decision attracted significant international attention. In this post, I will explain why the decision was made, the benefits it offers, and why, overall, the Danish pension system is strong—arguably among the best in the world. That said, it is not without its challenges. In my next post, I will explore the issues facing the Danish system and discuss potential solutions.

When Denmark increased its retirement age to 70 on 22 May 2025, it made headlines around the world:

*) BBC (link): Denmark to raise retirement age to highest in Europe.

*) CNN (link): Denmark raises retirement age to 70 — the highest in Europe.

*) The Independent (link): ‘Unrealistic and unreasonable’: Outcry as Denmark’s retirement age to become highest in Europe at 70.

*) And so on.

But why did Denmark make this decision? As Co-Director of the Danish Pension Research Centre (PeRCent) and author of this blog (Rangvid’s Blog), I feel it is my duty to inform you about the reasons behind this decision, its background, and the lessons that other countries might learn from it.

In this post, I will focus on the benefits of the decision and, more broadly, on the strengths of the Danish pension system. This will be a positive overview—because it is, indeed, a good system.

However, no system is perfect, not even the best ones. So, in my next post, I will discuss the challenges that the Danish pension system faces and how, in my view, they might be addressed. Stay tuned.

The decision to raise the retirement age

When I was interviewed by CNBC.com about Denmark’s decision to raise the retirement age to 70, the journalist’s first question was whether the decision had come as a surprise. I explained that it was no surprise at all. In fact, it was highly anticipated because it stems from a 20-year-old political agreement—known as the ‘Welfare Reform’, passed by the Danish Parliament in 2006—that links the state pension age to life expectancy.

The details of the reform are as follows:

*) The state pension age is set based on the latest recorded life expectancy for 60-year-olds, minus a target pension period of 14.5 years.

*) The state pension age can be raised by a maximum of one year at a time (i.e. there is a cap on increases) and is rounded to the nearest half-year when adjusted.

*) Adjustments to the state pension age are decided every five years in the Folketing (Danish Parliament), with 15 years’ notice.

It’s worth noting that, although international media (and I, for simplicity) refer to the ‘retirement age’, the reform actually links the age at which you become eligible for the state pension to life expectancy. The state pension (Folkepension in Danish) is a universal benefit for retirees, regardless of income or wealth. This means there is nothing stopping you from retiring earlier if you can afford to do so. The reform only dictates when you can start receiving the state pension.

Because of increased life expectancy—and because it was now time to take this decision—the Danish Parliament was scheduled to vote on a one-year increase in the retirement age on 22 May 2025. As most political parties had already indicated their support, the passage of the bill came as no surprise.

Currently, the state pension age in Denmark is 67. It had already been decided that it will rise to 68 in 2030 and to 69 in 2035. The decision made on 22 May raises it to 70 with 15 years’ notice, meaning it will come into effect in 2040.

Under the Welfare Reform, the Danish Parliament must decide again in 2030 whether to raise the retirement age to 71, which would take effect in 2045.

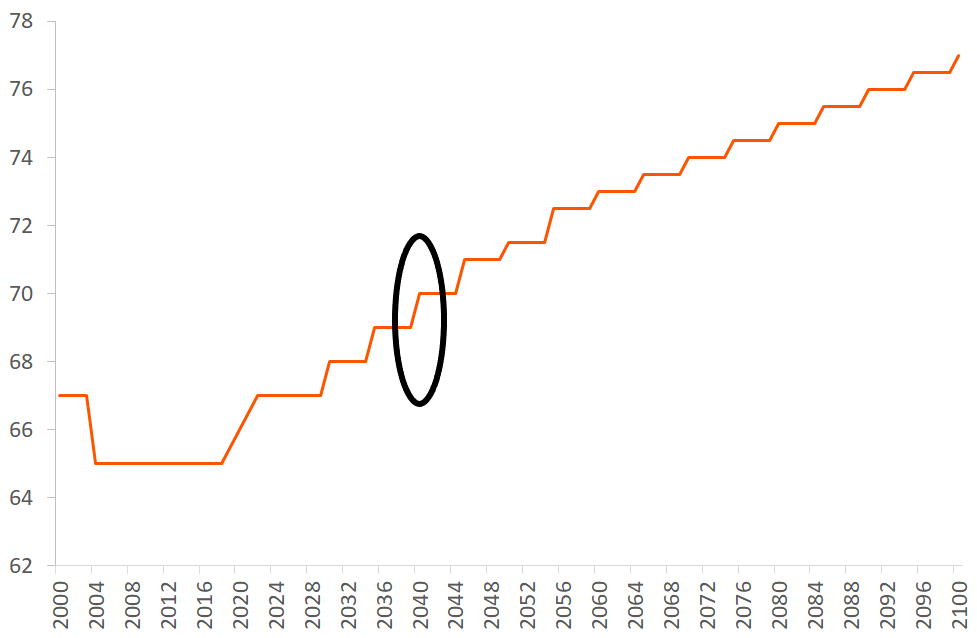

Figure 1 shows the expected future development of the retirement age in Denmark, based on current life expectancy projections.

Figure 1. Expected retirement age in Denmark. Source: Pensionskommissionen (link).

As you can see, by 2100, the retirement age is expected to be 77.

Consequences for public finances

The indexation of the retirement age to life expectancy is a cornerstone of Danish public finances. As people live longer, failing to adjust the retirement age accordingly would place a significant burden on public finances—a challenge that many (if not most) other countries are grappling with.

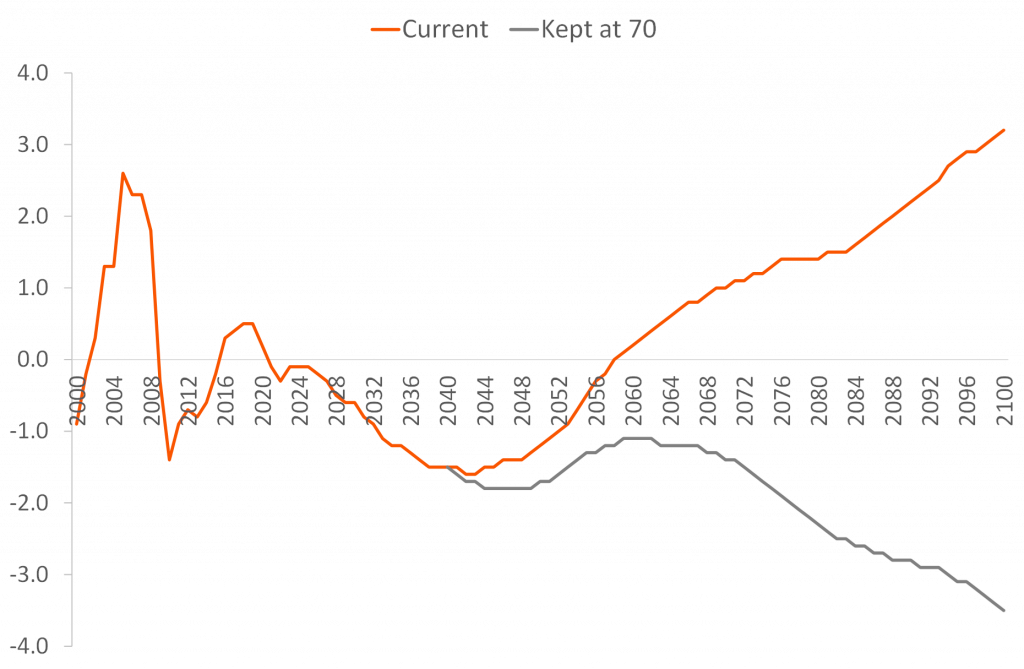

In Figure 2, I illustrate how the public deficit/surplus is projected to develop under two scenarios: one where the retirement age continues to rise as shown in Figure 1, and another where it is capped at 70 after 2040.

Figure 2. Danish public balances as a percentage of GDP, projected under current policy assumptions (including scheduled retirement age increases) compared to projections assuming the retirement age remains fixed at 70 after 2040. Source: Pensionskommissionen (link).

If Denmark continues to raise the retirement age as planned, the country’s public finances will remain very healthy in the long term, Figure 2 shows. In a recent blog post, I mentioned just how robust Denmark’s public finances actually are (link).

However, if the retirement age stops rising after 2040, public finances will deteriorate dramatically, as also shown in Figure 2. This is the problem many other countries face: without linking the retirement age to life expectancy, the burden on public finances becomes unsustainable. This is why the indexation of the retirement age is so crucial for maintaining sound public finances.

A strong Danish pension system: macro perspectives

The Danish pension system consistently ranks among the ‘best’ in the world (link), and has done so for many years. One key reason is the link between the retirement age and life expectancy described above, which secures the system’s sustainability.

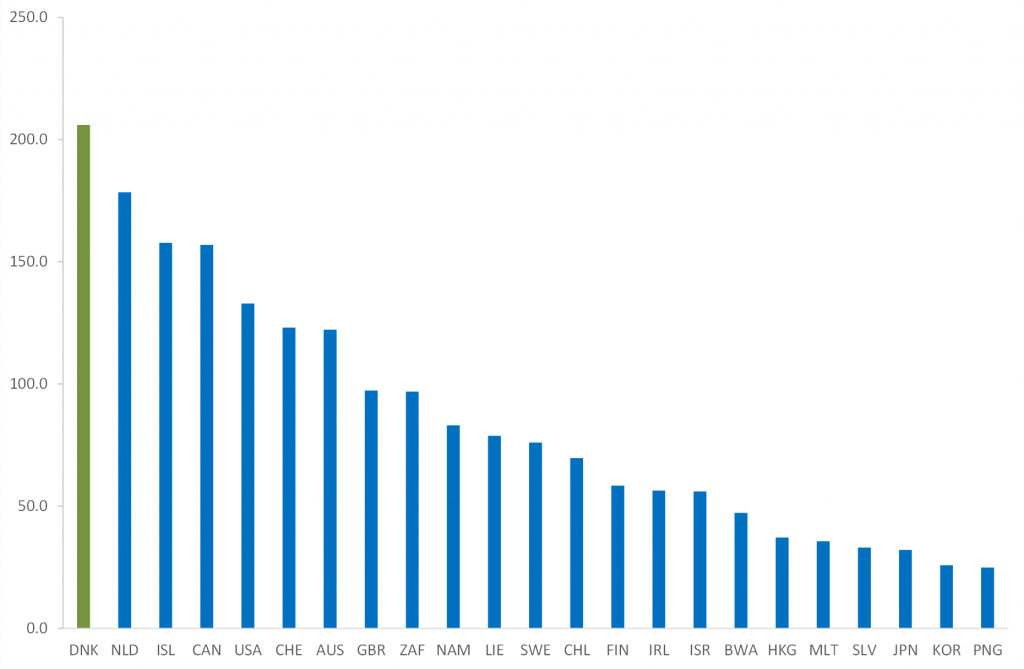

Equally important—if not even more so—are the high levels of private pension savings. Relative to GDP, Danish pension savings are among the largest in the world.

In a paper we published a couple of years ago (link), we compared private pension savings across countries, and at that time Denmark had the highest ratio of pension savings to GDP, as shown in Figure 3. This still holds true today.

Figure 3. Value of private pension investments to GDP (2015). Source: OECD.

Note also that a large proportion—indeed, most—of private pension savings is taxable during the payout phase. You can deduct your pension contributions from taxable income (thereby lowering your tax bill) in the year you make the contributions, but you must then pay tax when the pension savings are paid out during retirement. In other words, the state can expect substantial revenue when all these private pension savings are eventually distributed.

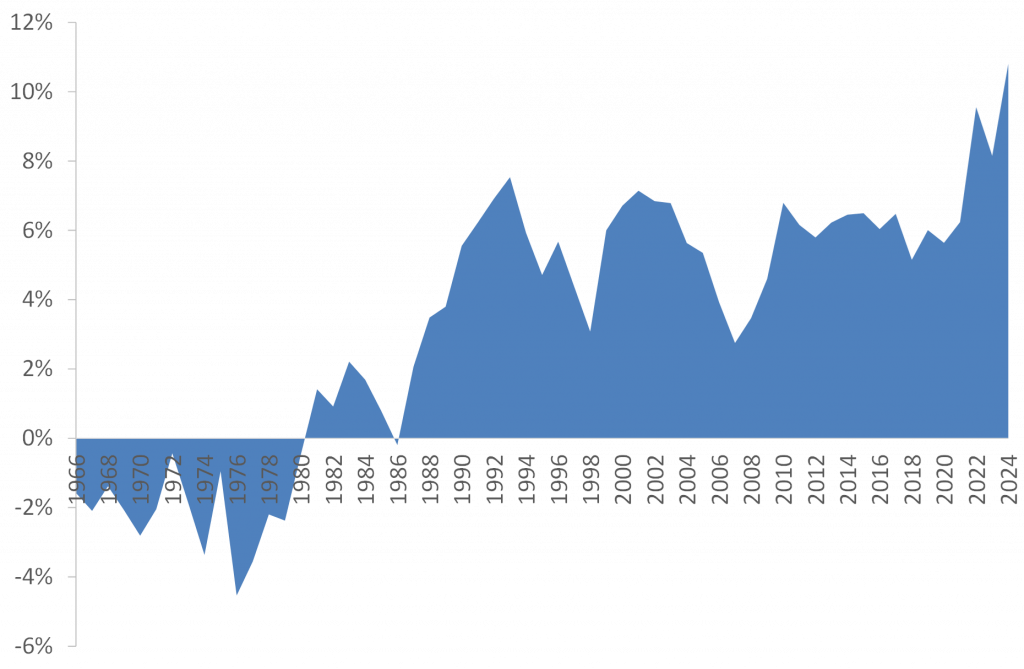

The build-up of mandatory, collectively agreed private pension savings since the mid-1980s has turned Denmark into a nation of savers. Denmark has gone from being a net borrower internationally—reliant on borrowing from abroad—to a net lender to other countries. This transformation is reflected in the dramatic shift in Denmark’s trade balance, as shown in Figure 4. As you know, a country’s current account of the balance of payments, mainly determined by the trade balance, is given by the country’s savings (private plus public) minus investments. So, when you increase private savings, you improve the current account, all else equal.

Figure 4. Danish exports minus imports, relative to Danish GDP. Source: Statistics Denmark

In the 1960s and 1970s, Denmark consistently ran current account deficits. Since the mid-1980s, however, Denmark has maintained consistent surpluses. While other factors have contributed to this dramatic turnaround, most economists—including myself—agree that the accumulation of pension savings has played the most significant role.

Today, Denmark boasts very sound macroeconomic finances, with strong public finances (see Figure 2) and a robust international investment position (see Figure 4).

Sound Danish pension system: micro perspectives

From a microeconomic perspective, the Danish pension system is also highly attractive.

Firstly, thanks to substantial private pension savings and adequate public pensions, most Danes can expect a sufficient income in retirement.

Last year, my co-authors Henrik Ramlau-Hansen, Mads Hebsgaard, and I published a study examining coverage ratios among Danish retirees (the study is in Danish, but you can find it here: link). The coverage ratio measures income in retirement as a percentage of pre-retirement income.

Most pension advisors recommend a coverage ratio of around 70–80%, as some expenses typically fall away once people stop working (for instance, households may no longer need two cars). A somewhat lower income in retirement is therefore acceptable, but not too low—hence the 70–80% guideline works well for most people.

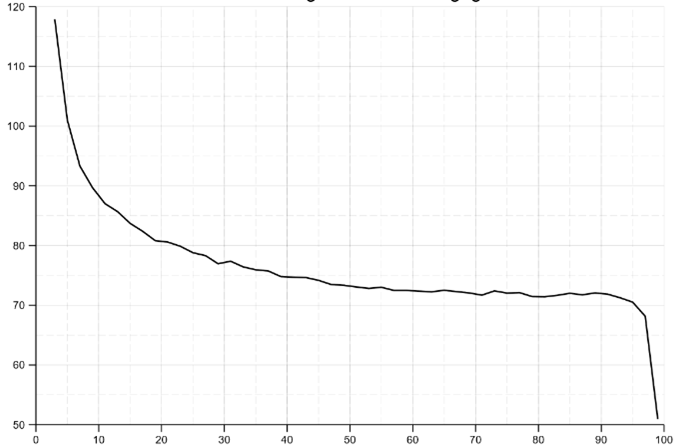

Figure 5 shows the coverage ratios of Danish retirees across the pre-retirement income distribution.

Figure 5. Coverage ratio defined as disposable income in the first year of retirement relative to average disposable income during the three years prior to retirement, shown across the pre-retirement income distribution. Source: Hebsgaard, Ramlau-Hansen, and Rangvid (link).

Most importantly, Figure 5 shows that more than 90% of retired people had a total disposable pension income—including public and private pension income, as well as any additional income during retirement such as financial returns—that exceeded 70% of their disposable income before retirement. In other words, the vast majority of Danes enjoy a healthy income in retirement.

Furthermore, coverage ratios are highest among those with the lowest pre-retirement incomes. This is because substantial public benefits (in addition to the state pension) ensure that those with the lowest earnings before retirement often experience an increase in their income after retirement.

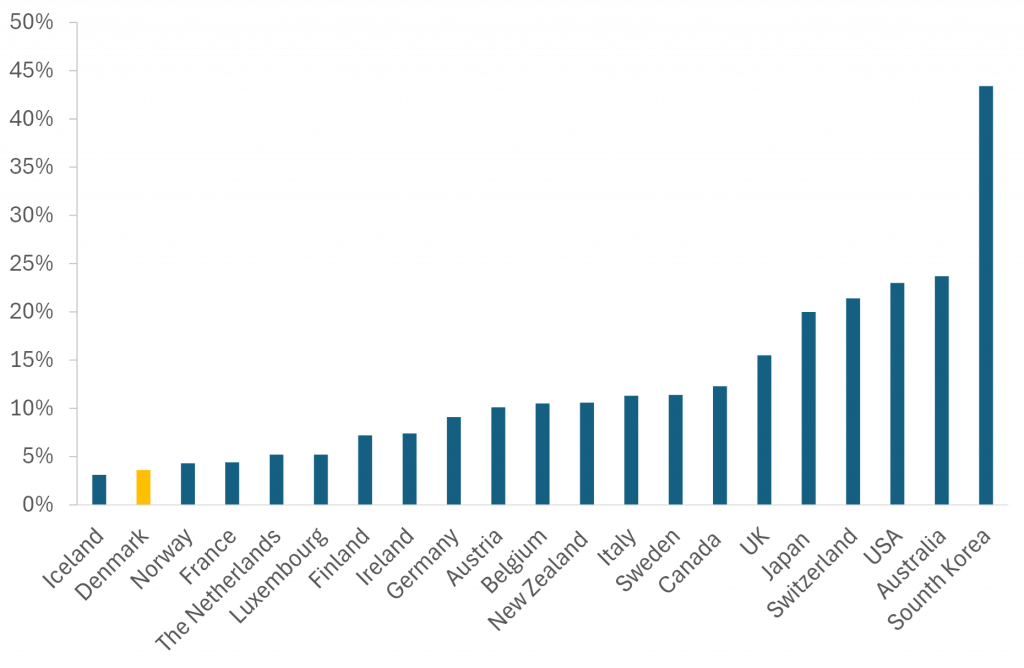

Moreover, the broad coverage of both public pensions and benefits, alongside private pension savings, ensures that practically everyone is guaranteed at least a basic level of income in retirement. This means that Denmark is among the countries with only a very small proportion of retirees classified as poor (defined as having a disposable income below half the median income in the total population), as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Share of adults above 65 with disposable income below 50% of the median disposable income in the total population. Source: Pensionskommissionen (link).

Finally, most Danes hold other types of savings beyond their pension funds—particularly residential savings, but also various financial assets. In our study mentioned earlier (link), we set out to estimate how much income Danes could potentially generate by converting their non-pension savings into retirement income. This includes selling stocks and bonds, drawing down bank accounts, selling property, or borrowing against one’s home—in essence, how much annual income could be derived from these assets during retirement.

Of course, such calculations require a number of assumptions (which I’ll spare you the details of), but the key point is that we have made what we believe to be conservative estimates.

We convert each individual’s savings into an annual income stream that can be added to their pension income, producing what we call total income—pension income plus potential income from other savings. From this, we calculate coverage ratios.

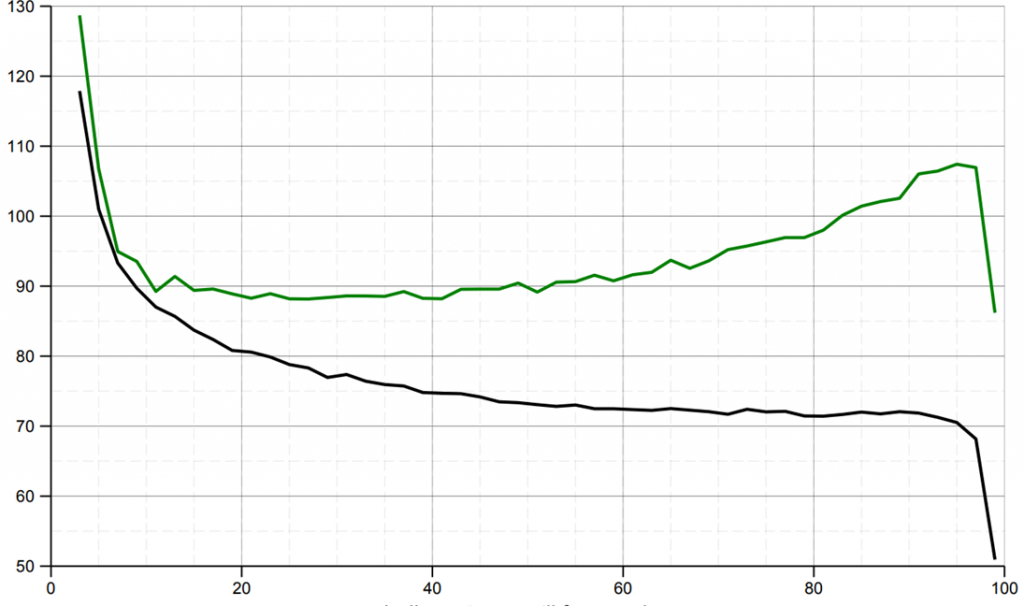

The results are shown in Figure 7, alongside the coverage ratios based on pension income alone, as previously presented in Figure 5.

Figure 7. Total coverage ratio (green line) defined as disposable pension income in the first year of retirement plus income that can be generated from non-pension savings relative to average disposable income during the three years prior to retirement, shown across the pre-retirement income distribution. Black line is coverage ratio based on pension income only, see Figure 5. Source: Hebsgaard, Ramlau-Hansen, and Rangvid (link).

As you can see, when considering all savings, practically all Danish retirees could generate retirement income exceeding 90% of their pre-retirement income.

Additionally, because financial assets tend to increase with income, the coverage ratios shown in Figure 7 also rise with pre-retirement income—except for those in the very lowest income brackets.

Conclusion

The Danish pension system is strong.

Thanks to the indexation of the retirement age—more precisely, the age at which you become eligible for the state pension—public finances are well positioned for the future.

Large private pension savings have transformed Denmark into a net international lender.

The combination of adequate public pensions and benefits, alongside substantial private pension savings, means that most Danes can expect sufficient income in retirement relative to their pre-retirement earnings. Moreover, very few elderly people in Denmark live on very low incomes.

All in all, the Danish pension system deserves applause.

However, not everything is rosy. Even Denmark’s pension system faces challenges, which I will discuss in my next post.