The United States is one of the richest countries in the world, and yet many Americans cannot expect a retirement income that matches their labour income. That is why BlackRock CEO Larry Fink focused on the retirement crisis in the US in his latest annual letter. But the solution may be just around the corner, as everyone is invited to be inspired by the Danish pension system.

It is thought-provoking that the US, which has produced amazing companies such as Amazon, Apple, Google, Microsoft, etc., is unable to build a well-functioning pension system, as BlackRock CEO Larry Fink argues in his recent annual letter to investors (link). Research by the OECD (link) shows that the US is not alone. What should the US and other countries facing similar challenges do?

How about taking a look at Denmark?

The purpose of this analysis is to explain the Danish pension system and invite anyone interested to take inspiration from Denmark on how to build a well-functioning pension system.

The Danish pension system

In Denmark, about 90% of the labour market is covered by defined contribution plans. Virtually all companies in Denmark have pension schemes that have been agreed either at company level or with the relevant trade unions. Participation is mandatory, i.e. everyone pays part of their salary into a tax-deferred account from the start of their employment. The size of the pension contribution depends on the company or area of employment, but is usually 12, 15 or 20% of salary.

We believe – and research shows (link) – that it is an important feature of the Danish pension system that participation is compulsory for all. Without mandatory participation, many will not start saving in time.

The aim of the system, together with the Danish state pension, is to ensure an old-age pension that represents a reasonable proportion of income during working life, i.e. a replacement rate of around 70-80% (pension in relation to pre-retirement income).

Defined benefit schemes were abolished many years ago in Denmark – the aim of companies should not be to cover investment and longevity risks.

Pension savings in Denmark takes place in pension funds or life insurance companies. Assets are invested according to the life-cycle principle, i.e. a large proportion of savings – often around 80-100% – is invested in risky assets (shares, private equity, etc.) at a young age, which gradually decrease to 30-50% by the (Danish) retirement age of 67. The life-cycle principle also continues in retirement, with the proportion of risky investments remaining stable or falling slightly.

The pension fund manages the investments, and the individual member has only limited influence. As a rule, members can only choose between a low, medium or high level of risk, if they have a choice at all. This means that savings are invested in well-diversified portfolios and ensures that everyone receives an “institutional return”.

Part of the pension system is that various death and disability insurances are integrated into the pension product and payments for these insurances (and for costs) are made through monthly deductions from the individual’s pension account. It is therefore not necessary to take out separate insurance policies, an advantage that ensures low insurance prices. The total annual cost of the Danish pension scheme is around 0.5-1.0% of savings, depending on the type of scheme.

Pension contributions are tax-deductible, but payouts are taxed on retirement. For many, the marginal tax rate on contributions is 56%, while 37% tax must be paid in retirement. Investment returns on savings are taxed at 15.3% per year, which is lower than the 27-42% tax rate on savings outside of retirement accounts. These tax advantages make pension saving attractive, an advantage that helps to secure support for the scheme.

When people retire, pension payments are spread over many years, in many cases for life, which is economically efficient for the individual and society. The individual is therefore not forced to buy a life-long annuity in retirement, another advantage.

Together with the means-tested Danish state pension, most Danes have a replacement rate of 70-80% when they retire, and this rate is expected to increase slightly in the coming years.

As in other Western countries, the Danish social security system is under pressure due to increased life expectancy. The Danish parliament has therefore decided to raise the current retirement age from 67 to 69 in 2035. It is expected that the retirement age will rise to over 70 in the future, which will ensure a long-term balance in the Danish economy.

Impact on the Danish economy

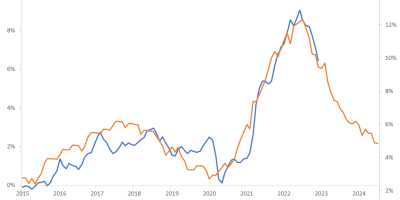

The system has been gradually expanded over the past 35 years. It is not yet fully developed, but pension assets are already about twice as high as Denmark’s GDP. This makes Denmark the country in the world with the largest pension savings in relation to the size of the economy, as Figure 1 shows. Figure 1 shows the 15 countries with the largest pension savings in relation to the country’s GDP in 2022 as well as the OECD average.

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance 2023 and J. Rangvid.

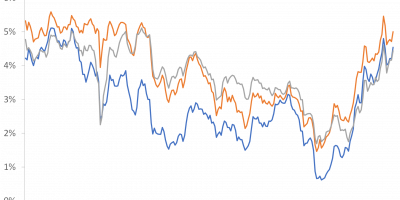

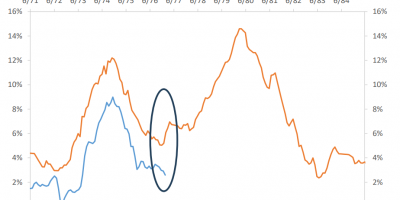

The pension system has contributed to Denmark’s transformation from being a net debtor in the 1970s and 1980s to being a net saver, which is reflected in substantial current account surpluses, as shown in Figure 2, and consequently in a strong net international investment position. The Danish pension system was developed in the late 1980s, coinciding with the change in the Danish current account balance from large deficits to large surpluses.

Source: Statistics Denmark and J. Rangvid.

There are several factors that contribute to the high current account surpluses in Denmark, but the large pension savings, and the returns on international investments of pension assets, certainly play an important role.

Finally, taxes on the income from pension savings also contribute significantly to the Danish state’s revenue.

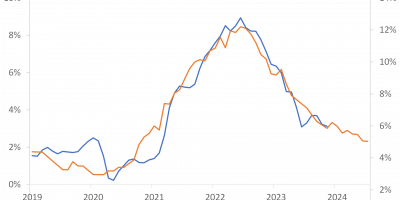

By way of comparison, the US has had large and persistent deficits in its current account, as Figure 3 shows, meaning the US has run up foreign debt over the past 40 years. Its Net International Investment Position was minus $20 trillion in 2023. This means that the US owed $20 trillion more to the rest of the world than ROW owed to the US. $20 trillion equals 73% of 2023 US GDP.

Source: Fed St. Louis and J. Rangvid.

Since the current account balance is the difference between savings and investment, the US will have to increase its savings rate at some point, for example by accumulating much-needed retirement savings.

In comparison, Denmark’s net international investment position at the end of 2023 was a positive 59% of Danish GDP. Foreigners owe Denmark more than Danes owe foreigners.

Conclusion

The Danish pension system is not perfect and there are still groups of the population who do not save enough. However, the Danish pension system contains many of the right elements of a well-functioning system: automatic and compulsory participation, lifelong investment according to the life-cycle principle, institutional returns and low insurance prices and costs. Overall, the system provides most Danes with an adequate income in retirement. We believe it is one of the best pension systems in the world and one that anyone can copy.

This analysis was co-authored with Henrik Ramlau-Hansen, a former CEO of Danica Pension (one of the largest pension companies in Denmark). Henrik is a member and I direct PeRCent (Pension Research Center) at Copenhagen Business School.