In many European countries, lock-downs have been comprehensive. Now that we have more data, it is time to ask the question whether all types of interventions are equally effective. New research indicates that restricting large gatherings and public events is effective. Restricting international and internal travel is not.

Given the fact that the number of new cases continues to fall in Europe, even when more and more is opened up (link), I cannot help wondering whether all types of lock-downs are equally effective. It must so that some measures are more effective than others are. And, if some measures are not effective, they should be applied with greater caution if we will face a second wave of the Covid-19 virus.

It is understandable that lock-downs were comprehensive early on, as data and studies on the effectiveness of different non-pharmaceutical interventions were lacking. Now we have more data. A new study is interesting in this regard.

Nikos Askitas, Konstantinos Tatsiramos, and Bertrand Verheyden (link) use data from 135 countries to study the effectiveness of different types of non-pharmaceutical interventions. By studying such comprehensive data, Askitas et al. are able to exploit variation in the timing, type, and effectiveness of interventions within and across countries in order to identify the effects of different types of interventions. The data also allow the authors to control for the contemporaneous influence of multiple non-pharmaceutical interventions, i.e. they can do their best to isolate the effect of each type of intervention.

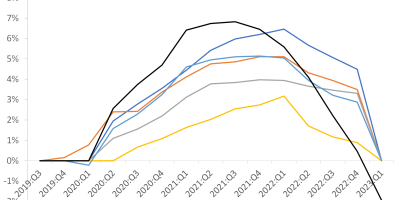

Askitas et al. classify interventions into eight different categories: (i) international travel controls, (ii) public transport closures, (iii) cancelation of public events, (iv) restrictions on private gatherings, (v) school closures, (vi) workplace closures, (vii) stay-at-home requirements, and (viii) internal mobility restrictions (across cities and regions). Their main results are here:

The figure reveals how the number of daily new infections develop prior and subsequent to the introduction of different types of interventions. The figure shows that the most effective interventions are cancellations of public events and restrictions on gatherings. For instance, 35 days after the introduction of interventions that cancel public events, the number of new infections has fallen by 25%, compared to the number of new infections at the event time, i.e. at the time of introducing the intervention, on average across the 135 countries in the study. The figure also shows that the effect becomes significant only after app. 20 days, i.e. it takes time before the interventions work.

On the other hand, international travel controls, public transport closure, and restrictions on internal (within country) movements seem to have basically no effect on the number of new cases. In fact, these types of interventions do not seem to have any statistically significant effect on the number of new infections.

School closures seem to have some effect, although it is barely significant.

Other authors have studied the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions, even when these studies do not look as carefully as the Askitas et al. study on the effectiveness of different types of interventions. Robert Barro (link), for instance, studies data from the 1918 Spanish flu, exploiting variation in the intensity and duration of interventions across US state. Barro finds only little effect of interventions. Barro also reports, however, that this no-effect result is most likely due to the short duration of the interventions implemented during the Spanish flu. Most of the interventions back then had a duration of around one month. The figure above shows that interventions only start being really effective after one month or so. In this light, it is perhaps not surprising that Barro finds only little effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions.

Other studies, for instance link and link, also report a positive effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions but do not estimate as clearly the effect of different types of interventions.

So, the conclusion, at least to me, is that:

- Non-pharmaceutical interventions can be effective, in particular if their duration is not too short.

- Some interventions are more useful than others are.

- In particular, restrictions of large gatherings and public events seem to be rather effective.

- Restricting international travel and public transportation does not seem to be effective.

Hopefully, results like these will be read carefully by politicians. If we will face a second wave of Covid-19, activities that do not influence how the virus spreads should not be shut down. On the other hand, we should be fast in implementing interventions that are effective, and their duration should not be too short. In particular, there is no need to uncritically just shut down “everything”. It is perhaps understandable that this was the approach taken in many European countries in March when evidence on the effectiveness of different types of interventions was missing. Today, we know more. Research indicates that it pays off to restrict gatherings of large groups of people, while restricting international travel and public transportation does not seem to pay off.