During the last couple of weeks, yields have been rising and stock markets falling. Standard market turbulence is not interesting for this blog – stocks go up and down, most of the time up, and yields fluctuate – but intriguing (and expected) patterns characterize recent events.

Everybody seems to agree what is going on markets these weeks: Vaccines are successful and being rolled out, so economies will open up soon, and Biden will get his stimulus package to the tune of USD1.9tn. These two things (an already strong economy when opening up and on top of that a large stimulus package) will lead to very strong growth during the second half of 2021. Inflation will rise and the Fed will have to tighten monetary policy. The expected rise in inflation and the policy rate leads to increases in yields today. This hurts stocks. These US developments spill over to other countries.

This story largely makes sense. Looking at the data, however, interesting outstanding issues remain.

The story

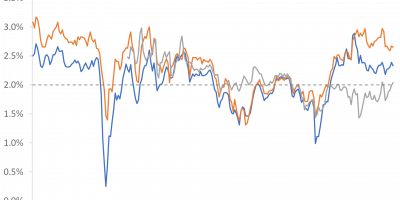

Inflation expectations have been on the rise since the start of the rally in April 2020. Figure 1 shows developments in expected average annual inflation in the US over the next five years and the yield on five-year Treasuries since April 1, 2020:

Source: Fed St. Louis Database

From a low level, expected inflation rose strongly during the summer-2020 rebound in economic activity, i.e. from April until August, and then stabilized. Since the election of Biden in November, inflation expectations have been on the rise again, because of the expected arrival of vaccines and the stimulus package.

Today, early March 2021, financial markets expect US inflation to be 2.4% per year on average over the next five years. Early November, expected inflation was 1.6%. An increase of almost one percentage point over the course of four months.

An expected rate of inflation of 2.4% is above the Fed’s target rate of inflation of 2% (link). With its new policy, the Fed might allow inflation to exceed 2% for some time, following a period of low inflation, such that average inflation over time approaches 2% (link). But how much more than 2% inflation will the Fed allow before it reacts? At 2.4%, markets start speculating that the Fed will raise rates to keep inflation expectations anchored.

Yields on 5-year Treasuries (also shown in Figure 1) had not moved until a few weeks ago. This also makes sense. As long as inflation is below the Fed’s two percent inflation target and the economy is suffering from the corona-recession, nobody expects the Fed to raise rates. As inflation started exceeding the target, expectations of a Fed hike started to be priced in.

Yields on one- and two-year Treasuries have not started rising yet, whereas yields on Treasuries with a maturity exceeding five years (five-year, seven-year, ten-year, twenty-year, etc.) have increased markedly during recent weeks. This means that the Fed is expected to start raising the policy rate in a couple of years only.

The rise in yields has caused turbulence on stock markets. Volatility (standard deviation of daily changes in the Nasdaq index, for instance) was 1.1% during November and December 2020 but 1.4% during January and February 2021. The same goes for the SP500 (0.83% during the last two months of 2020 vs. 1.04% during the first two months of this year). Stocks suffer.

Complications

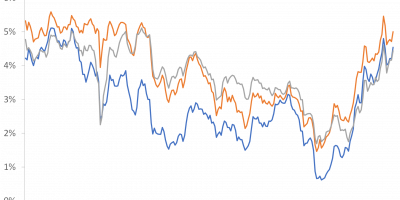

All this (yields rise when expected inflation exceeds the target of two percent) seems fine and makes sense. The complicating feature, however, is that ten-year yields (and twenty-year and thirty-year, i.e. yields on long-maturity securities) have been constantly rising in relation to shorter-term yields since markets calmed down in April 2020:

Source: Fed St. Louis Database

In April 2020, 10-year yields were 25 basis points above 5-year yields. Today, they are 80 basis points above.

It is thus not a new thing that yields rise. Longer-term yields have been doing so for some time. The new thing is that other yields start to rise, and that the increase in longer-term yields has accelerated during recent weeks.

We have just argued that it makes sense that markets start speculating that the Fed will raise rates when inflation exceeds two percent, and yields consequently react. But expected inflation over the next ten (and five) years has been below 2% ever since the start of the corona crisis and up until the turn of the year. Nevertheless, yields on ten-year (and longer) securities have been rising since April.

It is instructive to split expected inflation over the next ten years into expected inflation over the next five years and the subsequent five years, i.e. years 1-5 and 6-10 (the latter is sometimes called “5-year, 5-year expected inflation” or “5y5y expected inflation”):

Source: Fed St. Louis Database

Up until January 2021, expected inflation was generally below the 2% target rate of inflation. Shorter-term (1-5 years) expected inflation was lower than long-term expected inflation (6-10 years) but also rose faster. Still, ten-year yields rose while shorter-term yields did not.

Expected inflation over the next ten years is the average of the 5 year and 5y5y expected inflation.

The complication, thus, is that while it is fine and makes perfect sense that market reacts when expected inflation exceeds 2%, it is somewhat puzzling that some yields (longer-term) react when inflation is below 2% while other do not (shorter-term), even when shorter-term inflation expectations rise faster that longer-term expectations?

(Of course, other things, such as the real rate and risk premiums, determined yields, and I briefly discuss these below, but given that there is so much focus on inflation expectations these days, we need to complete that story first).

This issue is a little bit that either you say:

“Given that expected inflation was below 2% until December 2020, it makes sense that shorter-term yields were flat until the start of this year. When expected inflation over the next 5 years started exceeding 2%, 5-year yields started increasing and longer-term yields accelerated”.

Or you say:

“I believe ten-year yields have increased since April because inflation expectations have been increasing, recognizing that expected inflation was below 2%”.

You might be able to come up with a story explaining developments before January, i.e. long-term yields rising but not short-term, and expected inflation below 2%, but it is not straightforward. One story could be that people expected the Fed to keep rates low over the next couple of years, but raise them later. This story would not be based on expected inflation, though, as expected inflation was below 2%, both on the short and the long run.

Before corona

By the way, before we continue, there actually was some relation between expected inflation and yields before the corona crisis, as there generally is. Between autumn 2018 and the corona crisis, expected inflation was falling by close to half a percentage point:

Source: Fed St. Louis Database

And yields were falling, too, during the same period:

Source: Fed St. Louis Database

Real yields

Have real ten-year yields been rising between April 2020 and January 2021, explaining the rise in nominal yields? No. The fact that inflation expectations have been rising faster than nominal yields means that real yields have been falling since April 2020. And, the fact that shorter-term inflation expectations have been rising even faster than longer-term inflation expectations means that short-run real yields have been falling faster than long-run real yields:

Source: Fed St. Louis Database

Where should we look?

Given that the relation between expected inflation and yields is tricky (appears to be there now, but was muddy before January), it seems we need to think in terms of risk premiums. This is difficult. Perhaps the inflation risk premium has risen. Perhaps investors before January were more uncertain about inflation after five years than about inflation over the next five years, and demanded a compensation for this. It does not seem the most plausible story, but it is of course a possibility.

The obvious thing to shout is probably “debt”. It seems too early to go down that route, though. I present no analysis here leading credence to this story. And, there are many other potential explanations. It might be debt. But it might also be demographics, productivity, uncertainties, etc. There are many possibilities. The one that faces a hard time is trying to explain all developments in yields since the start of this rally by rising inflation expectations.

Last piece of evidence

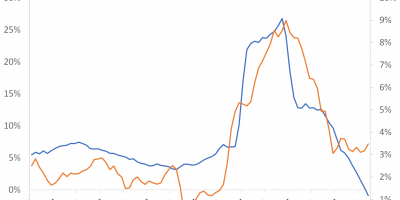

The fact that ten-year yields have been rising faster than short-term yields during this recession is not unusual. Historically, around recessions, ten-year yields rise more than short-term yields, either during or right after the end of recessions (sometimes even right before recessions). This is what we have been seeing since April. The slope of the yield curve becomes steeper around recessions:

Source: Fed St. Louis Database

The point I have been trying to make here is that the increase in the slope of the term structure (long-term yields rising faster than short-term yields) might not be unusual, but it is difficult to explain developments since April by simply saying “inflation is coming”. Expected inflation helps you explain some things, but not all.

Conclusion

Yields are currently going up because inflation expectations have started exceeding the 2% target rate of inflation. People start expecting the Fed to react at some point. This is fine and make sense. But inflation expectations have been going up for longer, since April 2020, and so have long-term yields, even when inflation expectations remained below two percent. Why did some yields (long-term) rise while others did not (short-term) when inflation was expected to remain below two percent and short-term inflation expectations rose faster than long-term expectations?