The evolution of inflation in the US in the early 1970s and today is strikingly similar, so we can compare the Fed’s actions then and now to see if it reacted more wisely this time. While the Fed forgot the lessons of the 1970s in the first phase of this inflation episode and waited too long to raise rates, it has reacted more sensibly in the later phase by not lowering the policy rate even though inflation has fallen. This gives us hope that we can avoid a severe second wave of inflation like in the late 1970s.

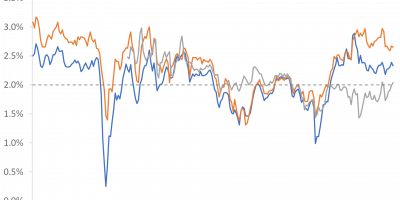

Last year I pointed out the strikingly similar inflation trends in the US in the early 1970s and today (link). In Figure 1, I update the figure to today.

Data source: St. Louis FRED and J. Rangvid.

Now, with more than a year of additional data, the trends remain similar. Inflation was consistently higher in the 1970s, but the trajectory of how inflation was stable before the flare-up, the duration of the flare-up, and the speed with which inflation has come back down are remarkably similar.

The last mile will probably be the hardest, as they say, but much has been achieved as inflation is moving closer to the 2% target, even if we have not quite reached it yet. Given that the target is in sight, and given the similarity of movements in the 1970s and today, it is interesting to compare how the Fed reacted then and now.

I wrote in the beginning of last year (link): “The Fed needs to keep a steady hand on the tiller. Despite calls to reduce rates soon, because the economic outlook darkens, the Fed needs to keep rates high enough for long enough. The 1970s taught us that not doing so resembles a “kick of the can down the road” approach, and the subsequent price to pay becomes so much higher.” Let’s see if the Fed has followed that advice.

Monetary policy

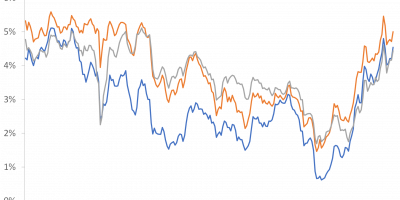

Figure 2 compares the fed funds rate in the early 1970s and today. Figure 2 is constructed in the same way as Figure 1, i.e. the lower and upper x-axes are identical in the two figures, but Figure 2 shows the fed funds rate instead of inflation.

Data source: St. Louis FRED and J. Rangvid.

The interpretation of Figure 2 is that if the Fed had reacted the same way today as it did in the 1970s, we would have two similar lines for the fed funds rate then and now. Instead, we see two very different lines in Figure 2.

In the early 1970s, the Fed reacted immediately. As soon as inflation began to rise in 1972/1973, the Fed raised interest rates. In fact, the Fed began raising rates a few months before inflation took off.

While this inflation cycle has developed exactly as it did in the 1970s (Figure 1), the Fed has reacted quite differently (Figure 2). In the early phase of the inflation cycle in the 1970s the Fed raised rates, while it lowered them in the early phase of the current cycle (in 2020, because of Covid-19). And, whereas in the 1970s the Fed continued to raise rates as inflation rose, it kept rates at 0% during the current inflation episode, even as inflation rose in 2021.

It was only at the point in the inflation cycle where the Fed began to cut the federal funds rate in the early 1970s that the Fed began to raise the rate today. The Fed began cutting rates in July 1974, when inflation was about to peak. This time, the Fed began raising the federal funds rate in March 2022, when inflation had also peaked.

So in the 1970s, the Fed started to raise rates when inflation was rising and lowered them again when inflation started to fall. This time, the reaction was exactly the opposite: the Fed cut rates and kept them very low (at zero) when inflation started to rise, and started to raise rates when inflation started to fall. There is certainly something paradoxical in this. Has the Fed forgotten the lessons of the 1970s?

Real Fed Funds Rate

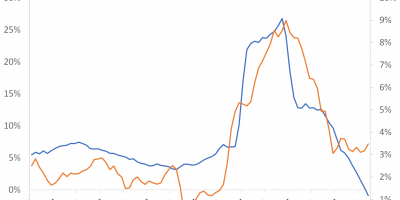

These reactions mean that the real fed funds rate – defined here as the simple difference between the fed funds rate and current US inflation – fell sharply in the first phase of this inflation episode, but has since risen to a higher level than in the same phase of the inflation cycle in the early 1970s. This can be seen in Figure 3.

Data source: St. Louis FRED and J. Rangvid.

Figure 3 shows that the real fed funds rate fell to -8%(!) in early 2022 because inflation was so incredibly high and the fed funds rate remained at 0%. In other words: At a time when inflation was enormously high, monetary policy was very loose. This was certainly not the Fed’s best time.

On the other hand, and much more positively, because the Fed has kept interest rates at the current level of 5.25%-5.5% even as inflation has fallen rapidly, the real fed funds rate has risen in the later part of this inflation cycle, and more so than in the same phase of the cycle in the early 1970s. The real fed funds rate remained in negative territory (i.e., the fed funds rate was lower than the inflation rate) as inflation declined in 1975 and 1976. Today, as inflation has declined, the Fed has kept the fed funds rate at a higher level than current inflation. As Figure 3 shows, the Fed funds rate has been about 2 percentage points above the inflation rate since autumn 2023, whereas it was negative in the same late phase of the cycle in the early 1970s.

Inflation in the late 1970s

It is positive that the Fed currently keeps the policy rate above the inflation rate, because experience from the 1970s shows us that interest rates were lowered too quickly back then. Figure 4 adds inflation up to June 1984 to Figure 1.

Data source: St. Louis FRED and J. Rangvid.

The second wave of inflation in the 1970s was even worse than the first. Inflation peaked at 15% in March 1980. One reason that inflation became so entrenched in the late 1970s was that monetary policy was too before the second oil price shock in the late 1980s, as I have argued in previous analyses (link).

As a result of the very high inflation in the late 1970s, fuelled not least by the expansionary monetary policy in the 1970s, the Fed had to pursue a draconian monetary policy and raise the Fed Funds rate to almost 20% and keep it at this level for several years, as Figure 5 shows.

Data source: St. Louis FRED and J. Rangvid

In fact, the fed funds rate did not rise above inflation until the late 1970s/early 1980s, i.e. only then did the real fed funds rate move into positive territory, as Figure 6 shows.

Data source: St. Louis FRED and J. Rangvid.

Figure 6 also shows that the Fed kept the fed funds rate roughly in line with inflation during the 1970s, i.e. the real fed funds rate was 0%, and only introduced a tight monetary policy at the end of the 1970s. In the 1980s, the Fed kept the fed funds rate 5-7 percentage points above the inflation rate, as Figure 6 shows, to fight inflation and restore the Fed’s credibility.

The tight monetary policy that had to be implemented in the early 1980s caused the severe recession of 1980 (link). So the need to tighten monetary policy so much because monetary policy had been kept too loose for too long was very costly. It would have been better if the Fed had pursued a tighter monetary policy in the 1970s.

The Fed’s current reaction of keeping stable interest rates despite falling inflation is a good one. It shows that the Fed has learnt from the 1970s that interest rates should not be cut too quickly when inflation is falling. This gives reason to believe that we could avoid a second severe inflationary spurt like in the late 1970s.

Conclusion

This is not the first time I have written about inflation in the 1970s and today. It’s such a fascinating topic because the current inflation cycle is so strikingly similar to what we experienced back then. And since the inflation flare-up in the early 1970s was handled so poorly, it’s interesting to see if we do better this time around, i.e. what we have learnt and what we have forgotten.

Inflation is now close to the target, and we can begin to assess how monetary policy reacted as inflation approached the target. That is the new point in this analysis.

The conclusion is that the Fed reacted very late in the first phase of this inflation cycle. It seems that the Fed had gone dormant and forgotten what to do when inflation picks up, probably because we had become used to inflation being so low before the pandemic.

On the other hand, the Fed is doing much better now, i.e. in the late phase of this inflation cycle. The Fed is keeping the federal funds rate at a fairly high level, even though inflation has declined significantly. In the early 1970s, the Fed lowered the federal funds rate as soon as inflation fell. That was not good, because monetary conditions were then too expansionary when inflation picked up again in the late 1970s. The Fed does not want to repeat this mistake. That is a positive realisation.