What a year. Inflation fell as fast this year as it rose in 2021 and 2022, we avoided an otherwise highly anticipated recession, stock markets did well but were dominated by a handful of stocks and central banks lost trillions of dollars and euros. I recall five important lessons we learned during 2023.

1. This inflation episode is strikingly similar to previous ones

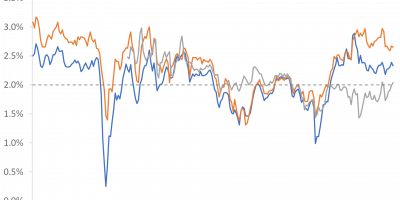

In my first analysis in 2023, in January, I compared inflation during this episode with that of the 1970s. I found that they were remarkably similar (link). I speculated whether inflation would continue to follow the same path in 2023 as in the early 1970s. It did. In Figure 1, I update the chart I showed in January. Throughout 2023, inflation has continued to follow the same trend as in the early 1970s.

Source: FRED of St. Louis Fed and J. Rangvid.

So far, so good. Inflation is approaching the 2% target, even if core inflation, sticky-price core inflation, shelter inflation and so on are still too high, differences that I have also analysed in 2023 (link).

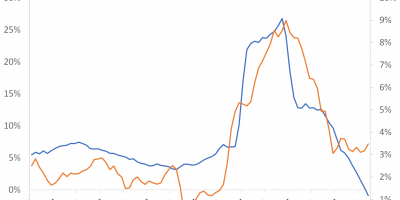

We must hope that central banks do not declare victory and cut interest rates too soon. This could trigger a second wave of inflation, as happened in the 1970s, see Figure 2.

Source: FRED of St. Louis Fed and J. Rangvid.

I examined long-term historical inflation data (link). I found that there have been four periods of high inflation in the USA in the last 150 years: World War I, World War II, the 1970s, and today. I noticed that there were two waves in two of the three first episodes, the one during World War II and the one during the 1970s. Figure 3 compares the current inflation episode with these earlier episodes. The big question today, of course, is whether we will see a flare-up of inflation again.

Source: FRED of St. Louis Fed and J. Rangvid.

A historical regularity does not necessarily mean that history will repeat itself. One big difference between the Second World War, the 1970s and today is that central banks today can learn from the mistakes of the past. A second difference is that central banks have inflation targets today, i.e. their main focus is on keeping inflation low. This hopefully means that we will avoid another flare-up of inflation. So this brings us to the first lesson from 2023:

Lesson 1: Today’s inflation developments are remarkably like past ones. The big question for 2024 (and beyond) is whether we get a second inflation flare-up, as has been the norm in the past.

2. Central banks are practically insolvent

Central banks have had a painful few years.

Their main goal is to keep inflation low, but inflation has skyrocketed. For too long, they argued that inflation was only temporary, so they raised interest rates too late. When they finally did raise rates, inflation was far too high and they had to raise rates very aggressively. When interest rates rise, bond prices fall. Bond investors lose money.

Central banks have invested heavily in bonds during several rounds of Quantitative Easing in the past. These bonds have now lost value, and a lot of it.

I analysed the losses of the Fed and the ECB (link, link, link). These losses run into the thousands of billions of dollars and euros. Figure 4 shows how the Fed’s losses and its capital have developed.

Source: Fed Annual Statements and J. Rangvid.

Central banks’ losses now far exceed their capital. The Fed, for example, had capital of 42 billion dollars at the end of 2022, while its losses totalled 1,080 billion dollars.

If a normal company incurs losses that exceed its capital, it goes bankrupt. How is it that central banks are not bankrupt?

Firstly, central banks argue that the losses in their bond portfolios have not been realised. This is true, but we learned in spring that even unrealised losses can lead to problems if they must be realised (link).

But even if central banks leave aside the unrealised losses from their bond portfolios, they still have to reckon with other realised losses.

Central banks receive interest payments on their bond holdings. The bonds were bought when interest rates were low, however, which means that interest payments are also relatively low. On the other hand, central banks’ expenses have risen. This is because the payments that central banks make on commercial banks’ deposits with central banks have risen alongside higher interest rates. So central banks expenses exceed their income. The reason is that there is a duration mismatch in the central banks’ balance sheets. The bonds central banks hold are long-term (and, as mentioned, were bought when interest rates were low), while the private banks’ deposits with the central banks are short-term. The bottom line is that central banks are losing money. So, again, why aren’t they bankrupt?

Here we come across the accounting practises of central banks, and they are dubious. For example, to cover its realised losses, the Fed simply creates an item on its balance sheet that “collects” the losses. The ECB twists (I call it, the ECB’s accountants will disagree) its balance sheet to show a profit of exactly zero euros! Obviously, such a result is not a coincidence. Academic research has shown that central banks tend to report profits of exactly zero instead of reporting negative results as a normal company would.

Central banks tell us that their equity capital is irrelevant. That is not true. If it did not matter, there would not be this concentration of profits of exactly zero (euro, dollar or whatever currency we are talking about). It will be interesting to follow central bank accounting in 2024. I will keep you posted.

Lesson 2: Central banks have lost a lot of money in 2022 and 2023. They care about these losses, even if they claim they don’t.

3. This was the most predicted recession that did not materialise

While the reputation of central banks has suffered greatly in recent years because they did not see inflation coming and because they are now losing money in trillions of dollars and euros, they will win a great victory if they manage to bring inflation down without triggering a recession. So far it looks good.

At the end of 2022, I wrote (link): “Weighting the pros and cons, I would be surprised if we avoid a recession during 2023. I would also be surprised if it turns out to be a severe one.”

Of course, you can always make your own excuses. For example, the largest economy in the eurozone (Germany) is in recession, so I was not entirely wrong. But I have to be honest. I, like most analysts, expected both the US and the wider eurozone to shrink in 2023.

My prediction was based on what we knew about the impact of monetary policy. I examined this evidence (link). A rough but not bad rule of thumb is that a one percentage point increase in the monetary policy interest rate lowers economic growth by one percentage point after one year.

Monetary policy rates were raised by 4-6 percentage points more than a year ago (depending on what country you look at), which means we should see 4-6 percentage points lower economic growth than without this tightening of monetary policy. 4-6 percentage points lower economic growth is a clear recession. That’s why we expected one.

However, it did not materialise. I had to analyse why (link). I argued that the main reason is that people still had a lot of savings left over from the pandemic. I found out that excess savings in the US peaked at around USD 2,000 billion, which is almost ten per cent of GDP (see Figure 5).

Source: FRED of St. Louis Fed and J. Rangvid.

If people have enough savings, they can pay the higher interest payments that result from tighter monetary policy, and monetary policy will not feed through to economic activity.

I also noted that these excess savings will be depleted in a few months (see Figure 5), which means that monetary policy will then start to bite.

While excess savings are the main reason we avoided a recession, other factors also played a role. For example, fiscal policy was very loose. This supported economic activity, but also meant that fiscal and monetary policy were uncoordinated. Tight monetary policy tried to tame inflation, while loose fiscal policy fuelled it. A third reason is that the proportion of adjustable-rate mortgages is low in many countries, which weakens the transmission of monetary policy to the economy.

Certainly, the chances of avoiding a recession are higher today than at the beginning of 2023, but I dare not yet declare complete victory. If central banks keep interest rates high because they are not sure that inflation is really under control, there could still be a recession. If, on the other hand, inflation is under control and central banks start to cut rates in 2024, we could avoid recession. That would be a great victory for central bankers. Let us hope for that victory.

Lesson 3: The economy has behaved differently this year than our evidence and theory would suggest. One lesson is that we need to pay more attention to savings when assessing the impact of monetary policy in the future.

4. Magnificent 7 dominated the stock market

And now to the stock market. Given that so many people had predicted a recession, the stock market’s performance in 2023 was impressive. The S&P 500 has risen by around 25% since the beginning of the year.

However, many companies in the stock market have performed poorly. The market was saved by a few stocks.

I analysed how important seven stocks were for the overall market (link). The result was astonishing. When I did the analysis in August, I found that the so-called “Magnificent 7”, or Mag7 – Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla – had been responsible for more than 70% of the rise in all 500 stocks in the index during 2023 (through August).

In Figure 6, I am updating the main chart to include all of 2023.

Source: Datastream via Refinitiv and J. Rangvid.

For 2023:

- The total market value of all 500 stocks in the S&P 500 has increased by $8 trillion or 24.2% during 2023.

- Without the seven Mag7 stocks, the value of the index would have risen by “only” USD 3 trillion, which corresponds to a return of 11.7%.

- The seven Mag7 stocks have caused the overall index to rise 12.5%.

- In other words, the Mag7s are responsible for 52% of the increase in the total market value of all 500 stocks in the S&P 500.

When I take stock here at the end of the year, Mag7’s performance is still impressive but less so than when I wrote my analysis in August. At the end of August, Mag7 had accounted for more than 70% of the value created by all the companies in the S&P 500. Today, that share has fallen to 52%. So it’s still a concentrated rally, but not as concentrated as it was right after the summer. The rest of the stocks have had a good autumn, as Figure 6 also shows. It will be interesting to see whether a few stocks will continue to dominate strongly in 2024, and if so, whether these will be the same seven stocks that dominated this year.

Lesson 4: Stock market gains this year have been heavily concentrated in a few stocks. We learned a new acronym: Mag7, or Magnificent 7.

5. Fundamental yields (r*) are still low

Finally, let me say something about yields. The yield on 10-year US government bonds reached 5% in 023, a level last seen more than 15 years ago, in 2007. People began to wonder if this (much higher rates) would be a new normal. I had my doubts. But doubts are not enough. So I looked at what we know about r*, the underlying equilibrium interest rate in the economy, i.e. the interest rate at which the economy is at its potential and inflation is stable.

Equilibrium yields have fallen continuously over the last four decades. The reason for this is higher savings and lower investment due to longer life expectancy, lower economic growth, etc.

I looked at the estimates for the future development of r* (link). The existing analyses are consistent. Virtually all of them suggest that r* will be relatively low in the future. Probably not as low as immediately before the pandemic, but lower than before the financial crisis, for example. I think Figure 7 summarises the findings well. It shows that if r* continues to follow expected economic growth, r* will most likely be relatively low in the future.

Source: NY Fed, CBO and J. Rangvid.

So, at least according to our latest academic research, we do not seem to live in a world where underlying equilibrium interest rates are significantly higher than we have become used to. A little higher, but not very much. A long-term level of equilibrium nominal interest rates of around 3.5% does not seem like a crazy bet.

Lesson 5: Even though central bank and market interest rates have risen sharply in recent years, underlying equilibrium interest rates still appear to be quite low.

Conclusion

2023 was another year of astonishing developments in the economy and financial markets. There were so many interesting developments to write about. I look forward to sharing new analyses with you next year.

I wish you all a Happy New Year.