Inflation in the Eurozone is historically high. One would expect that the European Central Bank (the ECB) would only talk about raising rates. Instead, they only talk about keeping rates low, in contrast to other central banks. Why is the ECB so strongly ruling out even the possibility that rates might be raised? Probably because there are highly indebted countries in the Eurozone that would suffer. The ECB is caught in a dilemma: Raise rates and risk that Italy (and other countries) will face debt-servicing challenges or keep rates low and risk that inflation remains too high. What to do?

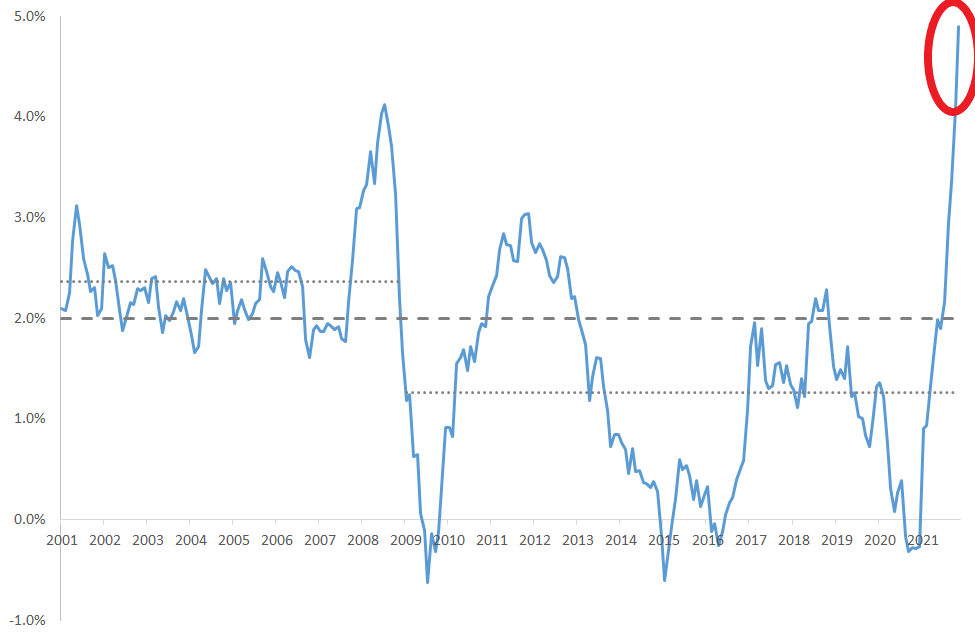

Inflation in the Eurozone is currently 4.9%, meaning that the Harmonized Consumer Price Index (HCPI) in the Eurozone in November 2021 was 4.9% above its level in November 2020. As Figure 1 shows, inflation has never been higher, at least since the Euro was introduced in January 1999.

Source: Fed St. Louis Database

ECB’s main task is to keep inflation close to 2% on the medium term. Its new monetary policy strategy introduced in July 2021 (link) slightly altered the goal-post from keeping inflation “close to, but below, 2% on the medium term” to “targeting an inflation rate of 2% over the medium term”. Prior to July 2021, ECB viewed inflation in excess of 2% as worse than inflation below 2%. Today, the ECB views an “inflation that is too low just as negatively as inflation that is too high” (link). The inflation goal is now symmetric. It is also clearer: What did “close to, but below” 2% actually mean? 1.7%? 1.8%? 1.9? A symmetric goal of 2% is clearer. So far so good.

In addition to the goal of 2% inflation (stippled line) and the actual inflation rate (solid line), Figure 1 also shows the average rate of inflation before and after the financial crisis (dotted lines). Since the financial crisis, inflation has typically been lower than target. The average is 1.3%. Again, it is unclear exactly what “below, but close to, 2%” actually meant, but most people view 1.3% as undershooting the target. Inflation has been too low over the past decade. Also in this light, 4.9% inflation is unusually high. After many years of too low inflation, I think the ECB would like to see inflation running a little higher than 1.3%. But not 5%.

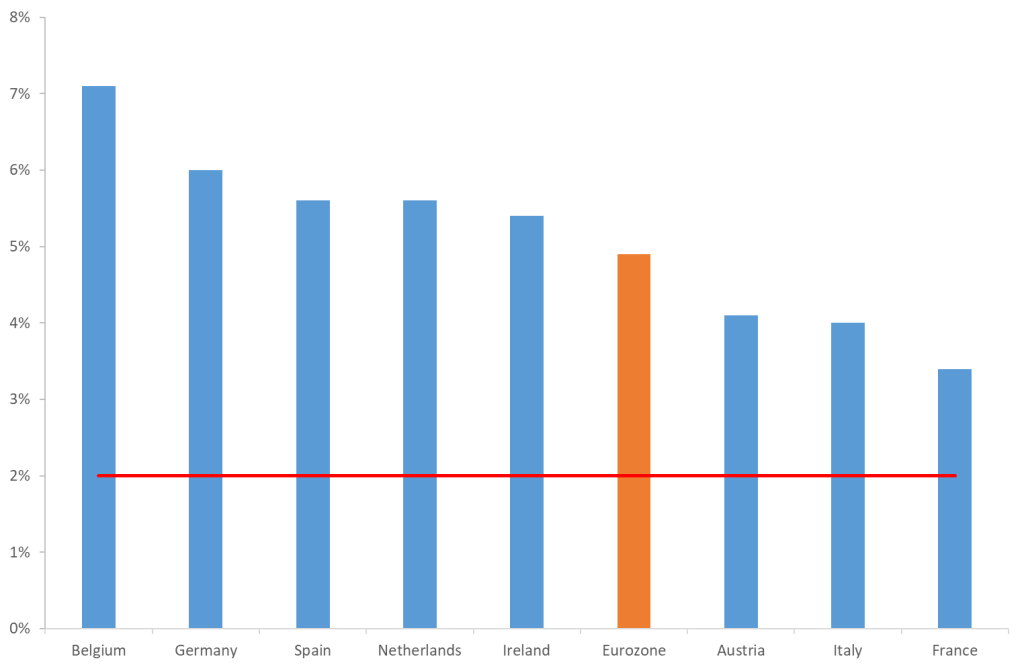

Adding further to the headache, inflation is not symmetrically distributed across the Eurozone. Figure 2 shows inflation rates in different Eurozone countries. Prices rise by more than 2% everywhere, but there are considerable cross-country differences. In France, inflation is “only” 3.4%, but in Germany, known for its inflation-resistance, inflation is running at 6%. No wonder my previous PhD colleague from Bonn Jens Weidmann is getting a little frustrated and has decided to resign from his role as President of the German Central Bank (link).

Source: Eurostat

High inflation is not only an ECB challenge. In the US, inflation is currently running at close to 6% and in the UK at 4%. In both countries, the goal is two percent inflation. Even in my own small country, Denmark, inflation is higher than it has been for many years, at 3.4%.

The US central bank (the Fed) has started reducing the pace of its bond purchases. It recently indicated that it will speed up tapering (reducing bond purchases) because inflation has surprised to the upside, lasting longer and staying higher than previously expected, paving the way for interest rate increases happening sooner than previously indicated. The Bank of England at its last meeting prepared markets that “it will be necessary over coming months to increase Bank Rate in order to return CPI inflation sustainably to the 2% target.”

We have seen no such statements from the ECB. In fact, the ECB strongly emphasizes that it is not even considering raising rates. As an example, ECB president, Christine Lagarde, early November made clear that it is “very unlikely” that conditions for raising rates during 2022 were in place, thereby effectively ruling out interest rate increases for next year (link). Christine Lagarde also indicated that bond purchases would continue. In light of inflation running at 5%, this is surprising.

Why does the ECB react so differently? Why does the ECB tie its hands? Why risk surprising markets if the ECB nevertheless has to raise rates?

The official explanation: It is temporary

The official explanation from the ECB goes along the following lines.

The goal of the ECB is to keep inflation close to two percent over the medium term (my emphasis). There are no explicit official statements explaining what “medium term” refers to, but think of it as a couple of years. This means the ECB does not have to keep inflation at two percent always and everywhere but may allow for temporary deviations from the two percent target. If inflation is only temporarily high, i.e. will return to its target within a reasonable horizon, the ECB should not react.

The ECB has made very clear that it believes current high rates of inflation are temporary. They say that economic growth has been very high since spring 2021, because pent-up demand from the Covid-19 lockdown was released when economies opened up during 2021, energy prices rise partly because of political developments that the ECB cannot influence, and supply-chains are strained because of Covid-19 related disruptions to transportation and production facilities. Furthermore, the story goes, when demand returns to normal and supply-constraints are removed, inflation will slowly – almost magically – return to target.

I agree that the strong economic growth we have witnessed during 2021 will not last. Most economic forecasters predict that growth will return to normal within the next couple of years. This should reduce part of the demand-induced inflationary pressures we are currently witnessing. On the other hand, this will not happen tomorrow. To illustrate, Figure 3 shows professional forecasters’ forecasts of economic growth in the Eurozone for 2021, 2022, and 2023, together with realized growth prior to the Covid-19 crisis.

Source: Expected growth from the Survey of Professional Forecasters from the ECB. Actual growth from Eurostat.

Economic activity is expected to expand by five percent this year and almost equally much next year, and then in 2023 normalize to the two percent growth that we saw prior to Covid-19. This means that growth-induced inflationary pressures will continue for a year or so, and then abate, the ECB argues.

Another crucial yardstick for the ECB is whether inflation expectations remain anchored. If people broadly understood (households, firms, investors) believe inflation is temporary, they will not start raising wages and prices. If inflation expectations on the other hand slip, there is a real danger of a wage-price spiral, i.e. firms increase prices, workers demand higher salaries to compensate for higher living costs, firms raise prices even more, and inflation runs out of control. This was the situation in the 1970s, and we really want to avoid that.

It is true that inflation expectations currently appear anchored. As this is important, I will show two types of inflation expectations. Figure 4 shows professional forecasters’ expected inflation for the calendar year in which the survey is conducted and the following year.

Source: Survey of Professional Forecasters from the ECB.

Professional forecasters believe inflation will be close to the ECB target this year and the next. They believe inflation will be a little higher this year than next year, i.e. high inflation is temporary, but, again, expectations are close to two percent.

In a survey, you ask people what they expect. We can also look at the money investors put on the table, or, rather, what is the expected inflation rate implied by financial contracts and trades. Inflation swaps are useful in this regard. Figure 5 shows the breakeven inflation rates implied by one-year, five-year, and ten-year Eurozone inflation swaps. The breakeven rate is the implied average inflation rate during the contract period, i.e. over the next year, next five years, and next ten years.

Figure 5 shows that expected inflation rates are at their highest since 2013, but not much higher than two percent. Near-term (one-year) inflation expectations are at three percent, but five- and ten-year inflation expectations remain anchored. Financial market investors also expect inflation to be short-lived.

Source: Datastream via Refinitiv.

A further argument from the ECB in support of very expansionary monetary policy is that Eurozone economic activity has not fully recovered from the pandemic, in spite of strong recent growth. To illustrate, Figure 6 shows Eurozone real GDP since 2015, together with a hypothetical growth path that assumes that there would have been no corona-crisis and economic activity would have expanded by the pre-crisis quarterly growth rate of 0.5%. According to this calculation, Eurozone economic activity is still EUR 100bn short of where it would have been, had there been no crisis.

Source: Fed St. Louis Database

The final argument from the ECB is that part of the underlying forces driving inflation are energy prices. And energy prices increase partly for political reasons, e.g., whether new pipelines (Nord Stream 2) will be approved. If gas does not flow to Europe, gas prices rise. ECB cannot do anything against this, the ECB argues.

A risky strategy

We might be lucky and everything plays out according to the ECB playbook. It is not impossible.

But there is an alternative, and I believe the ECB is too aggressively dismissing this alternative. The alternative is that inflationary pressures will not abate as much as the ECB expects. And by keeping monetary policy very loose – not even opening the door for tightening policies – the ECB is adding fuel to the fire.

The ECB has already admitted that their previous forecasts were wrong. For instance, ECB chief economist Philip Lane in an interview said (link): “The global recovery this year has been quicker than expected. In that context, of course bottlenecks can occur because supply is not keeping up, but that will be largely fixed next year. The fast recovery has also meant that energy demand has exceeded forecasts. Now the situation may last longer than we would like. Inflation is unexpectedly high at the moment, but we do think it is going to fall next year.” The emphasis is mine.

The ECB thus did not expect such strong growth, did not expect such high inflation, and did not expect inflation to persist. Nobody knows if the ECB is right this time. Perhaps. Perhaps not. If not, inflation might last longer than currently expected. I do not know either. But I argue that one should at least prepare for the possibility that this is not over tomorrow.

Furthermore, hoping that rising energy prices will not lead to persistent inflation is a dangerous strategy, when remembering the experiences of the 1970s. I do not want to indicate that we are going there again, but I do want to stress that the experience of the 1970s taught us that increases in energy prices might spill over to broader inflation measures and last for longer. For those interested in comparisons with the 1970s, I wrote this analysis a couple of months ago (link).

Third, it is true that economic activity has not fully recovered, as mentioned above and shown in Figure 6, but the labour market has recovered. More precisely, unemployment in the Eurozone is now at the same level as before the Corona crisis, at seven percent (Figure 7). Whether seven percent unemployment is satisfactory is a subtle matter, but it is a stylized fact that it has historically been difficult to get unemployment below this level, as Figure 7 also shows. Only right before the financial crisis, and right before the corona-crises, has unemployment in the Eurozone been as low as seven percent. A tight labour market fuels inflationary pressures.

Source: Fed St. Louis Database

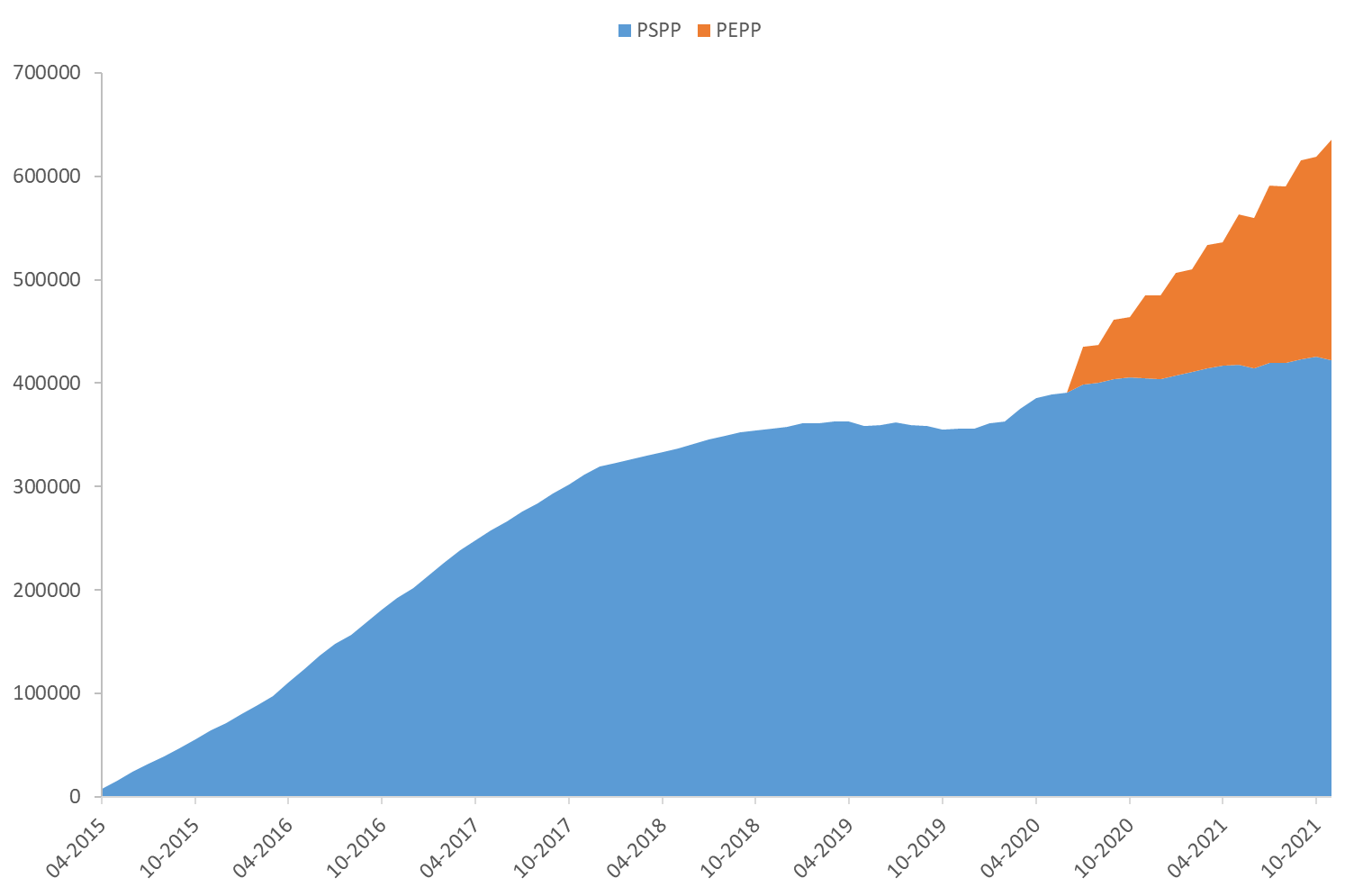

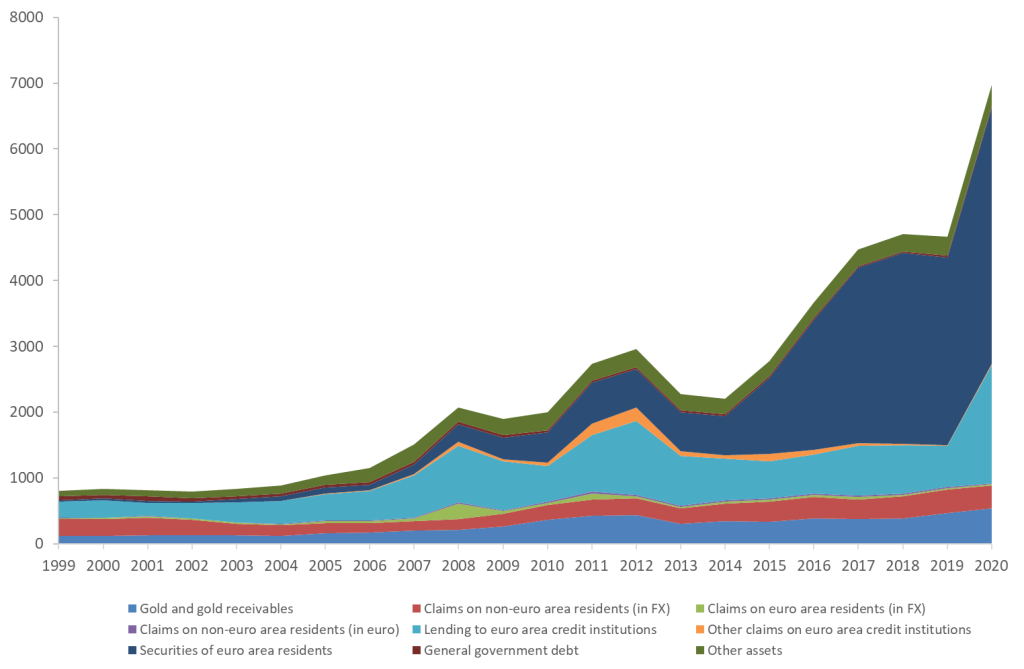

Finally, monetary policy is extremely aggressive. This adds to inflationary pressures. We have negative interest rates and enormous asset purchases. As Figure 8 shows, the ECB balance sheet was at EUR 2,000bn in 2014, rising by EUR 3,000bn over the course of three years as inflation remained too low (Figure 1), to EUR 5,000bn in 2017. From 2019 to 2020, i.e. over the course of one year with Covid-19, the balance sheet expanded by a further EUR 2,000bn, to EUR 7,000bn. Today, December 2021, assets worth a further EUR 1,500 have been added, and the ECB balance sheet stands at EUR 8,500bn.

Source: ECB

Will inflation abate or remain high?

Nobody knows. I believe that some inflationary pressures will abate next year, due to improvements in supply chains, lower growth, and more restrained energy prices. On this, I thus agree with the ECB. I am doubtful, though, that it will do the trick. It might be that inflation will return to a level lower than five percent. I even think this is likely. I am, however, doubtful it will return to two percent, in particular if monetary policy remains very loose. Leaving monetary very expansionary when inflation is already too high seem somewhat contradictory. I side with Jens Weidmann on this one. Briefly, it seems surprising that the ECB – at the very least – does not send strong signals that monetary policy might be tightened.

The ECB dilemma

Why does the ECB react so differently compared to other central banks, why does the ECB so strongly stick to the hypothesis that inflationary pressures are temporary, and why does the ECB not even open the door for clear reduction in asset purchases, paving the way for interest rate increases, should that be necessary? Why keep adding fuel to the fire when inflation is at five percent?

I think part of the reason is the following: The ECB is caught in a dilemma.

The ECB knows that very expansionary monetary policy, combined with already high inflation and strong economic growth, creates a serious risk that inflation and inflation expectations run wild.

The ECB also knows, however, that if it tightens monetary policy, i.e. stop asset purchases and raise rates, debt-burdened Eurozone countries will face severe challenges.

Take Italy as an example. At the end of last year, Italian public debt corresponded to 160% of Italian GDP. This is a lot of debt. Further, Italy did not succeed in bringing down debt when times were good prior to the corona crisis, in contrast to other Eurozone countries. Figure 9 shows public debt-to-GDP ratios for Italy, the Eurozone average and my own small country, Denmark prior to the financial crisis (2007), at the height of the Eurozone debt crisis (2013), right before corona (2019), and the latest annual figure (2020).

Source: Datastream via Refinitiv.

It is not strange that debt increases following a recession, such as following the financial crisis and corona. I.e., it is not strange that debt increased from 2007 to 2009 and from 2019 to 2020. What is noteworthy, though, is that Eurozone countries on average (and Denmark, by the way) were able to bring down debt when times were good – after the Eurozone debt crisis, i.e. from 2013 to 2019 – while Italian debt kept on rising.

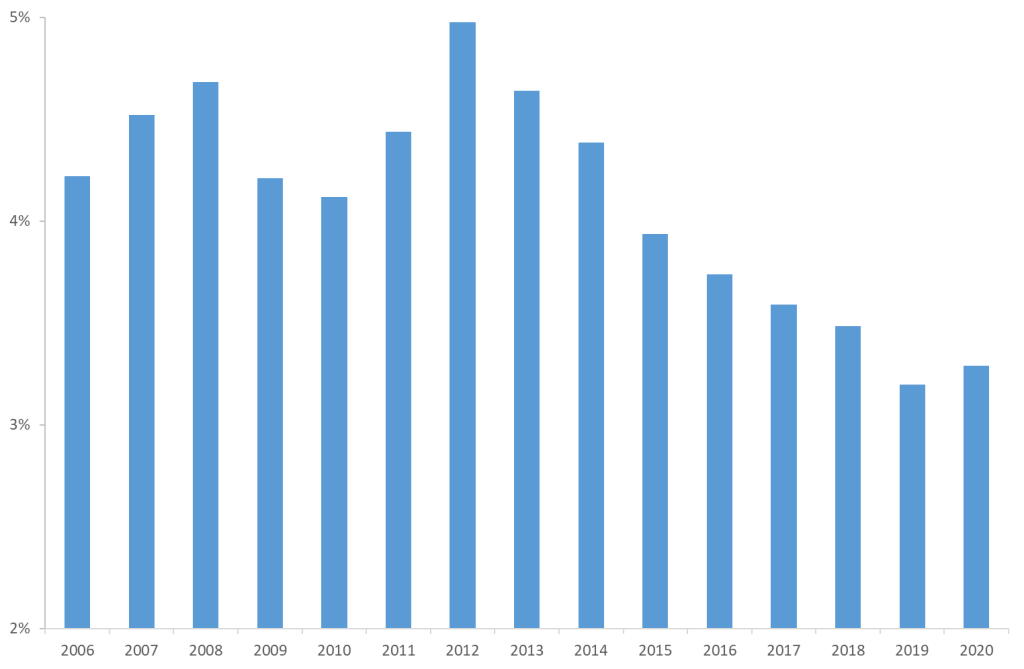

An intriguing feature here is that Italy, in spite of a massive increase in debt, in 2020 paid less in interest rate payments (as a fraction of GDP) than it did in e.g. 2007, as Figure 10 reveals.

Source: Datastream via Refinitiv.

In 2007, Italy paid debt-servicing costs amounting to 4.5% of GDP, while debt-to-GDP was at 104%.

In 2020, Italy paid debt-servicing costs amounting to 3.1% of GDP, while debt-to-GDP was at 156%.

So, in spite of a 50% higher debt burden, debt-servicing costs for Italy has been cut by a third from 2007 to 2020. The reason is of course low interest rates.

Interest rates have fallen globally. Countries with debt have all benefitted, including Italy. In addition to the global fall in rates, though, the ECB has been buying Eurozone government debt in massive amounts, significantly reducing rates even further. This is the point of the asset-purchasing programs, they should reduce rates.

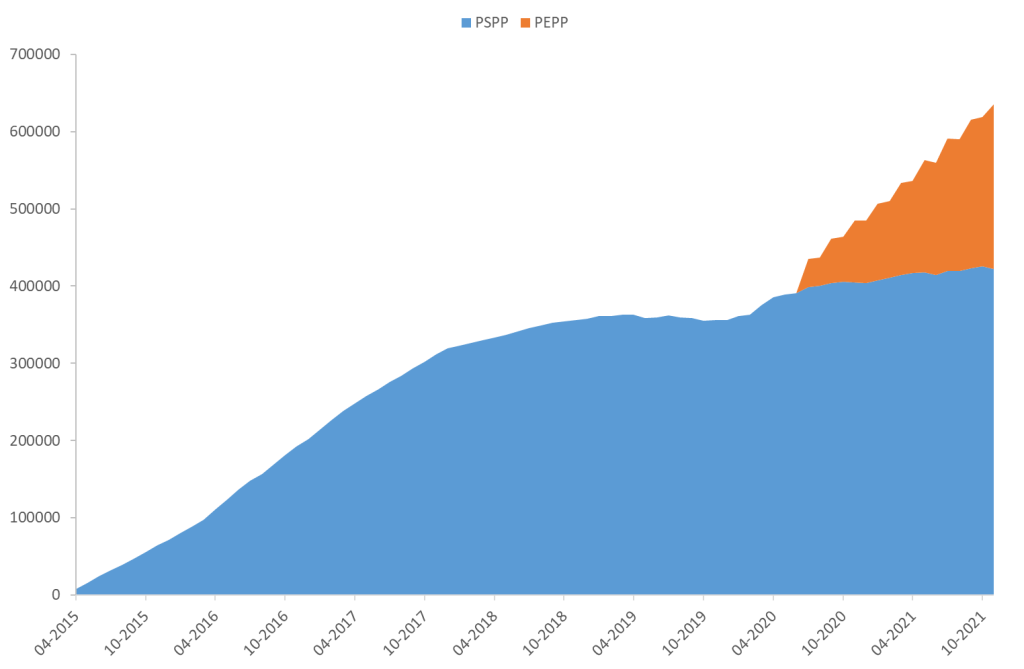

The ECB has bought a lot of debt. First, in relation to the Public Sector Purchase Program (PSPP), launched after the Eurozone debt crisis, and, second, in relation to the Pandemic Emergency Purchases Program (PEPP), the program launched to battle the corona crisis. Under the PSPP, ECB amassed Italian debt worth EUR 400bn. Under the PEPP, it amassed EUR 300bn. In total, the ECB holds Italian debt worth EUR 700bn, see Figure 11. The ECB owns close to 25% of all outstanding Italian public debt.

Source: Datastream via Refinitiv.

What would happen if the ECB stops buying Italian debt? Mario Draghi has made progress with respect to the Italian economy and thus probably increased investors’ belief that Italy can remain solvent, but it is a shaky situation and the ECB knows that.

Imagine Mario Draghi is replaced with an Italian politician who is less committed to reforming the Italian economy and whom markets do not trust. Imagine that the ECB stops buying Italian debt. And, remember that debt now stands at 160% of GDP in Italy. Italy will have a problem.

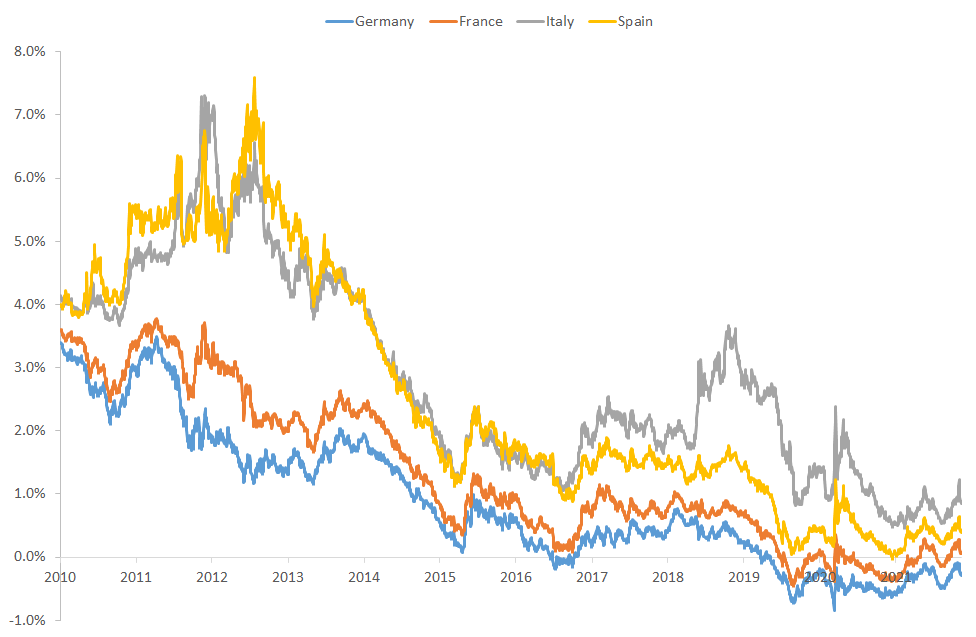

Many of us remember the Eurozone crisis in 2010-2013. Italian yields reached more than seven percent in 2012, see Figure 12. Yields only came down after Mario Draghi’s famous “we will do whatever it takes” speech in 2012 (link). ECB saved Italy, thereby saving the Eurozone.

Source: Datastream via Refinitiv.

Today, Italy is considerably more indebted than in 2012 (Figure 9). It seems likely that Italian yields would start rising significantly if the ECB stops buying Italian bonds. The Eurozone would be in trouble again.

This is not only about Italy. Debt is also high in other Eurozone countries. But debt is just so much higher in Italy (at 156% of GDP, compared to 120% of GDP in Spain GDP, in France 116% of GDP, in Belgium 114% etc. – public debt is even higher in Greece at 206%, but Greece is in a program and is, in all modestly, a small country compared to Italy). This is why we talk so much about Italy. The fact that it is not only a story about Italy only emphasizes the dimension of the dilemma, though.

The dilemma and other considerations

Let me be clear. I do not think that the challenges described above are the only reasons why the ECB is reluctant to talk about raising rates. Times are uncertain and there is a real possibility that inflation will fall going forward, even if I am doubtful that it will fall as much as ECB indicates. Also, I am particularly doubtful this will happen if monetary policy is not tightened. What I do believe is a true concern, tough, is that the ECB is stuck in a corner. Whether one fears this round of inflation will persist or not, the fact that the ECB is constrained by fiscal considerations is problematic. If the ECB one day needs to raise rates, it will face the dilemma described above.

What is the solution? This will take us too far in this blog, but it lies in the old discussion of macroeconomic reforms in certain Euroarea member states, directing fiscal policy to a healthy path, improving productivity and competitiveness, and in the end generate higher growth. This is easier said than done.

The solution might also lie in some form of debt sharing across Euroarea member states, thereby relieving the debt burden of highly indebted countries. This is also easier said than done. This involves tremendous political challenges. The EU has taken first steps, though, with the NextGenerationEU recovery package where the EU Commission, on behalf of the EU, will borrow money and distribute them to member states.

Conclusion

Inflation is historically high in the Eurozone. It might be that inflation will fall automatically next year, as economic activity is normalized and supply-chain bottlenecks resolved. This is the hope of the ECB.

I am in doubt. I am particularly in doubt that inflation in the Eurozone will return to target if the current stance of monetary policy is not altered. I am afraid that enormous asset-purchasing programs and negative interest rates are doing more harm than good in the current situation, that is a situation where inflation is running above target. In fact, I have been arguing for some time that monetary policy should be normalized (link). Now, these views gain traction and even the IMF recognizes that it is time to scale down very expansionary monetary policies (link).

The ECB knows that very loose monetary policy risks generating further inflation and creating asset-price bubbles. The ECB also knows, however, that if it tightens monetary policy, thereby raising interest rates, some Eurozone countries will run into trouble because their debt is very high. The ECB faces a dilemma.

Next week will be an interesting week in light of the discussion in this analysis. The ECB, the Bank of England, and the Fed will all hold policy meetings. The ECB will discuss whether to end the asset-purchasing program implemented because of the pandemic. I hope they will not prolong it, nor increase other asset-purchase programs. If they do, it risks further fueling inflationary pressures and asset-price bubbles. If they don’t, some countries might start shaking. What a dilemma.