In December I argued that inflation is too high but that the European Central Bank (ECB) faced a dilemma (link): Raise rates and high-debt countries will suffer, or keep rates low and inflation will remain too high. I concluded that the ECB should start raising rates. Inflation is now even higher, and the ECB faces an additional dilemma: Raise rates and risk derailing a recovery already suffering under the weight of elevated uncertainty and high energy prices, or keep rates low and inflation will remain too high for too long. Another worrying development is that ECB risks losing its grip on inflation expectations. What to do?

In February 2022 eurozone consumer prices were 5.8% higher than in February 2021, almost three times higher than ECB’s aim of two percent inflation.

Inflation increased this February because of rising energy prices in particular. However, inflation was already too high before the terrible situation in Ukraine and its effects on commodity prices. Inflation exceeded the two percent target in July 2021, only to continue increasing since then. In November 2021, for instance, inflation was running at 4.9%. Core inflation (overall inflation less the effects from volatile commodity and food prices) now runs at 2.7%, which also exceeds the two percent target, further emphasising that inflation is persistent and broad-based and not due to commodity prices only. It is by now clear that these price increases are not transitory.

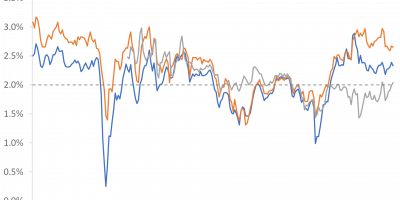

It is not surprising that inflation started rising in summer 2021. Since the financial crisis in 2008–2009, ECB has struggled to generate sufficient inflation. Figure 1 shows that inflation has been closer to one than two percent since 2009 on average. The figure also highlights the development in inflation since December 2021.

Data source: Fed St. Louis Database

Even though ECB has kept rates in negative territory since 2014, bought government bonds to the tune of billions of euros and implemented forward guidance, inflation did not move much. Then, in March 2020, the pandemic caused even lower inflation. Monetary and fiscal policies turned even more expansionary. We (households) couldn’t go out to eat or travel because of the lockdown. Savings increased. In spring 2021 vaccines became available. We began going to restaurants and enjoying life again. With high savings, we could afford to spend. The result was strong economic growth: four percent in 2021 in the eurozone. Normally, economic growth is around two percent. The labour market tightened. We got traditional demand-driven inflation. And when you add supply chain disturbances, very high inflation results. Nothing strange here.

But ECB’s decision to rule out the option of a tighter monetary policy, however, was strange. Perhaps we all hoped that supply chain bottlenecks would be resolved, but the underlying strong demand would still be there, and, on top of this, there are always risks. With inflation running at five percent at the turn of the year, and an exceptionally loose monetary policy, there was a real possibility that inflation would not revert sufficiently. I did not expect six percent inflation in February 2022, but I was in doubt that inflation would fall, as ECB asserted. I argued that the ECB should factor in the possibility that things would not go according to plan. The ECB did not agree, maintaining that it was “very unlikely” that rates would go up in 2022 (link). I will go so far as to argue that not preparing markets for at least the possibility that inflation might not automatically revert to target was a policy mistake.

But here we are. Few people believed that Putin would invade in Ukraine. I did not believe this either. I fail to see that this war is in the interest of Russia. Probably like most people, I believed that Putin would be rational. But he started a war, a terrible thing in all aspects of the word. And a negative shock to inflation.

It is important to stress that I – of course – do not blame the ECB for the rise in inflation that will result from the war. My point is that inflation was already too high before the Ukraine war, but the war has made things worse.

Risk management is not about trying to predict events but about having a plan if low-probability events occur. I believed that even without negative shocks there was a likelihood that inflation would remain too high. ECB strongly ruled this out. Then we got a terrible negative shock. Inflation is now even further away from target. The ECB faces a new dilemma.

Inflation expectations

In its arguments for continuing with expansionary monetary policies, the ECB emphasised that even if inflation was running above target, inflation expectations remained anchored. Alas, this is no longer the case.

Inflation swaps indicate that investors expect prices to rise by almost six percent over the next year. So current inflation is six percent (5.8%) and investors expect inflation to continue to be six percent next year. This is not good. Potentially even more worrying, though, investors expect inflation to remain high for several years. Figure 2 shows expected one-year inflation one year from now (1y1y) and expected inflation over the next two years, two years from now (2y2y).

Data source: Datastream via Refinitiv.

Expected inflation bottomed out at close to zero percent in March 2020. Since then, investors have raised their expected inflation, but stopped at two percent. The ECB could argue that inflation expectations were anchored.

This is not the case anymore. Figure 2 shows that investors now expect that one-year inflation one year from now (1y1y), i.e. from March 2023 to March 2024, will exceed 2.8% and that annual inflation from March 2024 to March 2026 (2y2y) will average 2.6%. This means that markets expect that the ECB will be unable to bring inflation back to target over the next three to four years. At 2.3% even average annual inflation over the five-year period starting in five years (5y5y) is elevated. Investors expect that Europeans will have to live with too much inflation for many years. If I were sitting in Frankfurt, I would be worried. There is a risk that the ECB is losing its grip on inflation expectations.

Oil prices

Inflation was too high before the war in Ukraine but has accelerated even further. The reason is the rise in commodity prices. You may have encountered graphs in newspapers depicting recent dramatic developments in commodity prices, such as the price of wheat, gas and oil. The situation with nickel was extreme (link). Figure 3 shows developments in oil prices, which are now (March 2022) 60% above their 1 January 2022 levels. Developments in gas, wheat and nickel prices are even more extreme.

Data source: Datastream via Refinitiv.

The question for the ECB (and for all of us, i.e. investors, analysts, politicians and ordinary people) is what this implies.

First of all, consumers and firms will face prices that continue to rise. We will see inflation moving even higher. I dare not make a precise prediction, but the percentage-point jump in inflation from January to February gives an indication of the kind of magnitude we are talking about.

High inflation supports that monetary policy should be tightened. But the rise in commodity prices also hurts people’s buying power. With nominal salaries not moving yet, inflation erodes real wages. This reduces aggregate demand and, in the end, price pressures in the economy. The question is how much. My view is that betting that inflation will automatically revert to target is a dangerous strategy.

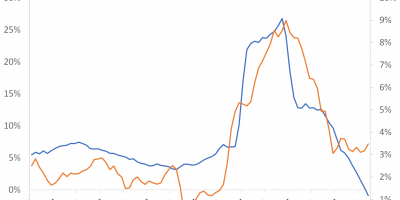

When discussing whether the increase in oil prices reduces aggregate demand, we tend to think back to the early 1970s. Even if the current situation bears some resemblance, there are important differences. First, as mentioned, the major part of the inflation we see now is not the result of the war in Ukraine. Inflation was 5% in November last year. Furthermore, oil and other raw materials are less important for economic activity than in the 1970s. Thus, there is reason to believe that the effect of oil prices on economic activity is less dramatic than back then. Figure 4 shows the absolute, i.e. dollar, change in the price of oil from the beginning of a year (January 1) to the beginning of the following year together with real growth in global economic activity from the first year to the next. Thereby, this is a predictive relationship. How much has world GDP changed from one year to the next in relation to how much oil prices have changed from the beginning of the year to the beginning of the next year?

Data source: World Bank and Datastream via Refinitiv.

During the 1970s, and potentially the 1980s, there was a negative correlation between changes in oil prices and subsequent changes in economic activity. When oil prices increased in 1973 and 1974, global economic growth subsequently suffered. The same was the case in the late 1970s.

Since the 1990s the correlation has been positive. This means that when oil prices have increased, global economic growth in the subsequent year has improved. How to interpret this? This blog post is not meant as an in-depth academic statistical analysis, with all the regressions that would entail, but my interpretation is that oil prices drove economic growth during the 1970s, while expected economic growth has been driving oil prices lately. So, in the 1970s, when oil prices rose, it reduced aggregate demand later on because firms reduced production and consumers reduced consumption. In recent years, expected demand has influenced oil prices. When we expect economic activity to blossom, we expect high demand for oil, which pushes up oil prices.

What does this imply for the current situation? As the world is now less dependent on oil, then recent increases in oil prices will not have as big an effect on economic activity, and thus on aggregate demand and price pressures, as earlier in history.

Second, the lesson from the bad experiences of the 1970s is that hope that inflation will automatically revert to target is dangerous. You perhaps recall that I wrote an analysis in August last year (link) examining whether 1970s-like inflation is coming back. I argued that it is not, based on the belief that we have learned something since then. I maintained that we have learned that, instead of accepting low real wages, people are demanding higher nominal wages when facing increasing prices. When nominal wages rise, firms increase prices even further, leading to a wage-price spiral. So, it might be that aggregate demand suffers from high inflation in the short run, but people do not sit on their hands. Lower real wages (resulting from high inflation) did not stop inflation in the 1970s, tight monetary policy did, as also described in the aforementioned post (link). We have learned that rates should be raised when inflation is too high.

ECB’s additional dilemma

All this creates a highly unfortunate situation for the ECB. On the one hand, it is clear what they should do. Inflation is too high, inflation will not come down automatically; monetary policy is loose, and inflation expectations are no longer anchored. The ECB needs to raise rates.

If the ECB raises rates, it might have negative consequences for some highly indebted sovereigns, such as Italy. I discussed this dilemma in December (link) and concluded that the ECB should nevertheless tighten monetary policy.

On the other hand, the terrible situation in Ukraine has increased downside risks in the economic outlook. Falling stock prices, reduced real wages resulting from high inflation, and elevated levels of uncertainty risk derailing the economic recovery. When rates are raised, monetary conditions tighten, leading to further downward pressure on economic activity.

Not doing anything, on the other hand, presents a real risk that inflation and inflation expectations will raise even further, causing all sorts of problems. This is an additional dilemma for the ECB.

What to do?

I am of the opinion, and have been so for some time, that the upside risks to inflation are too high. I thus vote in favour of sending signals and taking action. I am happy that ECB is finally taking some action (link), but it is too late and too little. Monetary policy is still too expansionary. In other words, monetary policy should be tightened more than ECB did at their March meeting (link).

Conclusion

Inflation in the eurozone is very high and has been for many months. Recently, the horrendous situation in Ukraine has contributed to increasing inflation even further. The ECB is confronting a new dilemma.

The consequences of the war in Ukraine (rising commodity prices, falling stock markets, high uncertainty) pose a material risk to the economic recovery in Europe. If the ECB raises rates to constrain inflation, it risks that the recovery will suffer even further. Hence, there is a risk of withdrawing monetary support too early. ECB remembers that it did so in 2011, right before the European debt crisis.

There is, however, also a risk of withdrawing monetary support too late. If monetary policy is expansionary when inflation is already high, inflation expectations rise, potentially causing developments that resemble those of the 1970s. We do not want that either.

I understand the dilemmas the ECB faces. In my view, the main issue is that inflation is so high now that it risks spiralling out of control. Even if there are dilemmas, I find that the ECB should tighten monetary policy.