Euro area countries share monetary policy but not fiscal policy. When inflation was low, the European Central Bank (ECB) could address challenges this created with “Whatever it takes” policies. With sky-high inflation, this is much more difficult. Comparing euro area with non-euro area EU countries leaves one wondering whether the common monetary policy has incentivized some euro area countries to pile up too much sovereign debt, creating dilemmas ECB cannot solve.

It took ECB too long to recognize that post-pandemic inflationary pressures were not short-lived. ECB argued that increasing oil prices and supply-chain challenges resulting from the pandemic would vanish automatically, meaning monetary policy rates could be kept low. As late as November last year, when euro area inflation was running at 5%, ECB chief Lagarde said it was “very unlikely” that rates would be lifted in 2022. What a misjudgment.

When companies see their costs increase, due to, e.g., higher oil prices, they pass on those costs to customers, and inflation spreads throughout the economy. We learned this the hard way in the 1970s. We also learned that if such inflationary threats are not addressed by resolute monetary policy, broad-based inflation results.

And here we are. Inflation is running at more than 8% in the euro area. Core inflation, inflation less energy and food, is also vastly exceeding ECB’s 2% inflation objective.

ECB was not the only central bank that misjudged the inflation process. But ECB is the only one that has not lifted rates yet. Or, to be more precise, among those central banks that face high inflation, ECB is the only one that has not lifted rates.

To illustrate, Figure 1 shows the ECB deposit rate and the Fed Funds Target (average of the Upper and Lower limits for the Fed Funds Rate) since the beginning of the year. While the Fed has raised rates three times already, ECB rates are stuck at -0.5%.

Data source: St. Louis Fed and ECB.

Now, you might argue that the situation is different in Europe (compared to the U.S.), in that energy prices matter more for inflation in Europe. While this is true, I have argued elsewhere that this does not mean ECB should not raise rates, because core inflation is rising in Europe, inflation expectations are showing worrying signs (link), and energy price inflation might spread if no action is taken (link).

You might still not like the comparison with the Fed in Figure 1 (or you might like it). Let us compare with other central banks, then. Figure 2 shows the increase in monetary policy rates in percentage points during the past year, and the number of times monetary policy rates have been hiked, for a number of comparable central banks. For instance, Figure 2 shows that Fed has lifted rates (the upper band of its Fed Funds corridor) from 0.25% a year ago to 1.75% today, an increase of one and a half percentage points (blue bar). Fed has raised rates three times (orange bar). Bank of England has lifted rates by 1.25 percentage points over five rounds. And so on.

There are no bars for the euro area. This is because ECB has not lifted rates, in contrast to other central banks.

Data source: Central bank webpages of the different countries.

Bank of Japan has not lifted rates either. This makes sense, however, because Japanese inflation is only slightly above target and core inflation is below one percent (link). In contrast, in the euro area, inflation is 8% and core inflation 4%, making for a similar situation as in Norway, Sweden, U.K., and the U.S. In those countries, central banks have recognized the challenges and started to address them. ECB has not.

Monetary policy vs. fiscal policy

The reason ECB is behind the curve is obvious. As soon as ECB started indicating that rates might be lifted, yields in Italy rose.

ECB faced, and is still facing, a dilemma (link): Raise rates sufficiently to contain inflation, but risk Italy (and potentially other countries) run into fiscal challenges, or keep rate hikes moderate, thereby helping Italy, but risk inflation becomes de-anchored.

In 2012, when Italian, Spanish, and other sovereign yields rose, ECB saved the euro by implementing broad-based asset purchases. “Whatever it takes policies”, it was called. Because inflation was too low, these expansionary policies also helped ECB fulfill its inflation mandate.

Today, inflation is much too high. ECB urgently needs to raise rates, but if ECB starts massive purchases of Italian sovereign bonds, to help contain the rise in Italian yields that results from higher monetary policy rates, such purchases will increase financial-market liquidity and work against the monetary policy objective of reducing inflationary pressures.

You might do tricks. You might buy bonds and sterilize their effects on financial-market liquidity. Such tricks are no long-term solution, however.

The fundamental challenge is that fiscal policy positions of individual euro area member states make it harder for common monetary policies to work as intended.

This is no new dilemma. The founders of the euro recognized it. Rules were made, restricting debt levels and government budget deficits, such that common euro area monetary policy could work independently of fiscal policy conditions in individual member states.

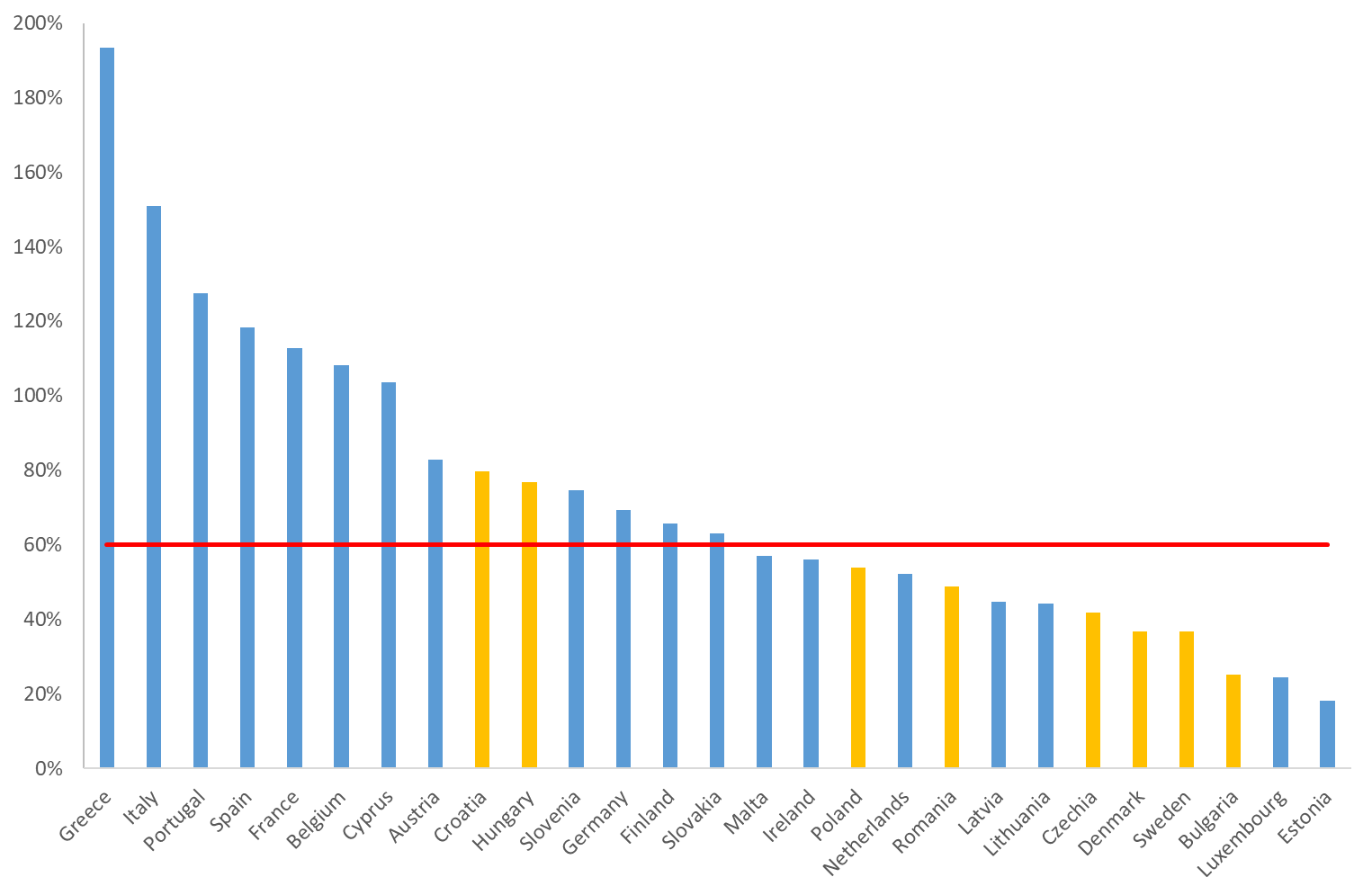

The problem is that these rules were never adhered to. The Maastricht Treaty debt/GDP limit is 60% (this is of course the same debt limit as in the Stability and Growth Pact). Try comparing the number of euro area countries that fulfill this criteria (blue bars in Figure 3) with the number of non-euro area EU members (yellow bars) that do fulfill it.

Data source: eurostat.

12 out of 19 (63%) euro area countries do not fulfill the Maastricht criteria. I.e., outstanding government debt exceeds 60% of GDP in two out of every three euro area countries, in spite of the Maastricht Treaty/Stability and Growth Pact.

On the other hand, only 2 out of 8 (25%) non-euro area EU countries do not fulfill the criteria.

This means that more non-euro area EU countries (relative to the total number of non-euro area EU countries) manage to keep their debt levels low, compared to euro area countries.

Probably this is no coincidence. Correlation is not causality the saying goes, but it seems a reasonable hypothesis that the incentive to keep debt levels low is limited when a common central bank is ready to buy debt in unlimited quantities should challenges arise.

When ECB says “We will not tolerate changes in financing conditions that go beyond fundamental factors and that threaten monetary policy transmission” (link), the incentive to keep debt levels low is limited, and it will become more complicated to bring inflation under control.

I disagree that there are “non-fundamental forces” at play currently. I view it as a “fundamental factor” that investors become nervous when rates rise in a country that has a lot of debt. I am worried that if ECB wants to prevent rates from rising on Italian debt, because ECB believes it is not a “fundamental factor”, ECB takes away the pressure to keep debt levels low.

What is the solution?

One can muddle through. This is the current situation. Monetary policy does not respond as it should to inflationary pressures in the euro area because of fiscal policy considerations. Extended periods with too high inflation, hurting economic growth and prosperity in the euro area, will result. This is called stagflation.

Or, one can address the fundamental challenge. There are two possibilities.

Take the Maastricht criteria seriously. This is no easy task. Getting debt levels down to Maastricht Treaty levels would require severe fiscal tightening in many countries, hurting economic growth in years to come. Politically, it might not be acceptable.

The alternative is a move towards some sort of common fiscal policy. This might not be as crazy as it sounds. EU countries have started moving down this path with the EU Next Generation Fund (link). The fund makes unilateral transfers from Brussels to individual countries, with funds raised by common debt issuances. Thereby, effectively, Italy borrows Germany’s higher debt credibility. Doing more of this would help Italy finance its debt at low costs.

This is, of course, no straightforward solution either. It is easy to imagine the headlines: Thrifty Germans pay for spendthrift Italians. But it would liberate ECB from fiscal policy considerations, allowing monetary policy to address its main target: inflation.

Conclusion

For the second time in ten years, euro area monetary and fiscal policy objectives clash again. In 2012, inflation was low, so ECB could address it with “whatever it takes policies”. Today, inflation is very high. It is apparent that it is difficult for ECB to implement the right monetary policy because ECB has to pay too much attention to fiscal policy challenges. Perhaps it is time to address the dichotomy caused by common monetary but individual fiscal policies.