One year ago, as central banks and most analysts thought inflation was temporary and things would be fine, I argued housing and stock markets were overvalued (link), and that they would fall when interest rates rose. Since then rates are up, stocks are down, housing markets suffer, and the global economy is on the brink of a recession. Finally, I said the risk of a 2008-like financial crisis was low. During the past month, however, no less than three events have threatened financial stability: The LDI crisis in the UK, the problems in Credit Suisse, and the bailout of the European energy sector. Is it accidental that all these things happen at the same time, or is it a forewarning of what is to come?

A year ago I posted an analysis arguing that expansionary monetary policies and low interest rates had driven stock and housing markets to bubble-like territories (link). I also warned stock and real estate markets would suffer when central banks raised rates. A few months later, in early 2022, the Fed started raising rates, and other central banks followed. Since then, stocks are down some 20-25%.

Stocks are down because interest rates are up and the likelihood of a recession has increased. And, circularly, the likelihood of a recession has increased because interest rates are up.

In my analysis I also argued that the probability of a 2008-like crisis was low. I wrote: “This means we should avoid a 2008-like event”. This is still my best guess. However, recent events have presented a challenge to this sanguine view.

Prelude to the 2008 global financial crisis

Do you remember what happened on August 9, 2007? If I tell you that BNP Paribas suspended mark-to-market valuations of three of its hedge funds, most of you probably still do not remember what I talk about.

The financial crisis started on September 15, 2008, when Lehman Brothers defaulted, didn’t it? You could say so, but we had the first indications of what was to come already one year earlier. Liquidity had started to dry up. BNP Paribas dramatically wrote (link): “The complete evaporation of liquidity in certain market segments of the US securitization market has made it impossible to value certain assets fairly regardless of their quality or credit rating.” Here is a good description of this event (link).

People analyzed the situation and convinced themselves that this was not of systemic importance and could be dealt with. Central banks injected liquidity. We relaxed. Unfortunately, the problem was more fundamental. The events foretold what was to come.

Currently, severe events–all characterized as “threats to financial stability” by the relevant authorities–are happening almost weekly. It seems they are idiosyncratic events, accidentally happening at the same time. Maybe. Maybe not. One can’t stop wondering whether they, like in 2007, are forewarnings of what is to come.

Three worrying events

During recent weeks, we have witnessed a number of events that (i) were dramatic and sudden, (ii) largely unexpected, and (iii) make one wonder whether the system is as sound as we keep on telling ourselves. I will spend most of my time on the first, as this is the most interesting, but the sum of them makes one alert.

First event: UK and the LDI

The first event was the chaos following the presentation of the “mini-budget” by the new UK Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng on September 23 and the consequences this had for liability-driven investments (LDIs) in UK pension funds.

The new UK premier minister Liz Truss had promised tax cuts, and tax cuts we got. Unfortunately they were unfunded and no plan was presented on how to deal with the hole in the budget they created. Normally the Office for Budget Responsibility assesses what such plans imply for future public finances, but the Chancellor seemingly rejected such an assessment (link).

Markets became nervous, and yields on UK sovereign bonds rose. Had this been it, so be it. But things got out of control because of risky investment strategies in UK defined-benefit corporate pension plans.

Consider a pension fund that has promised to pay out GBP 100 in 30 years. The best hedge of such a liability is to buy a bond with a face value of 100 that matures in 30 years. Unfortunately the yield on that bond has been low for many years, and pension funds are underfunded. So, instead of buying a bond with face value GBP 100 that matches the liability of GBP 100, pension funds invested in a combination of bonds (with face value less than GBP 100) and risky assets, in the hope that such a risky portfolio would generate higher returns. The problem is that when you move away from buying the 30-year bond with face value GBP 100, you expose yourself to the risk that you cannot honor you obligations. This is where LDIs enter the scene.

Pension funds hedge this liability risk, i.e. the risk that funds cannot meet their obligations because of movements in interest rates and inflation, with derivatives. The challenge is that these derivatives require funds post collateral. Pension funds post UK gilts as collateral. The mechanics of the hedging contracts are such that if the value of the collateral falls, you have to post more collateral. This is called margin calls. In the case of LDIs, the margin calls had to be met with cash payments.

So, as interest rates rose and bond prices mechanically fell, because of the irresponsible “mini-budget”, pension funds had to raise cash to meet margin calls. Pension funds sold their UK gilts. They had to sell a lot of them, because the funds have entered into a lot of LDIs. The market could not readily absorb the selling pressure – liquidity was not sufficient in the sense that funds could not offload all these bonds without affecting the price of the bonds. Bond prices fell even more, and so did the value of the collateral. Pension funds received even more cash-calls. They had to sell even more bonds. Prices fell further. It was a serious situation.

The somewhat ironic thing is that increases in yields reduce funding pressures in pension funds in the long run, as it lowers the present value of pension funds’ future liabilities. Unfortunately, the long run does not always help in the short run. Here, in the short run, pension funds had to raise lots of cash because of margin calls, in spite of them being more solvent in the long run.

If you are interested in a good and “pedagogical” explanation of LDIs, that is as pedagogical as such an explanation can be, here is one (link). And here is a somewhat more geeky description of events (link).

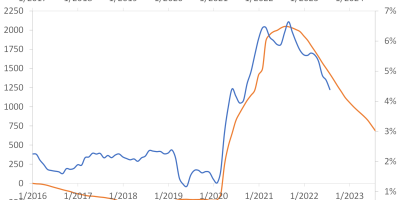

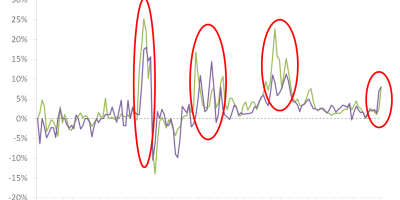

The rise in yields was dramatic. During 2021, Italian and UK spreads to German bonds were similar, Figure 1 shows. During the first half of 2022, the Italian spread widened, while the UK spread stayed flat. This changed with the launch of the “mini budget”. UK yields rose dramatically, reaching Italian levels (encircled in Figure 1). UK bonds started trading at a premium of two percentage points to German bonds.

Imagine this. The riskiness of UK sovereign bonds is on par with the risk of Italian bonds. Some probably find it amusing. I find it sad.

Data source: Datastream via Refinitiv.

This was no small disruption. The Bank of England warned against “material risk to UK financial stability” (link). “Material risk to financial stability” is a warning of something like 2008. And, remember, the UK gilt market is not some small market. London is an important global financial hub.

Some people had warned about the inherent risks in LDI strategies, but it is fair to argue that it was not considered a major issue by most observers. Most people outside the UK pension industry had not heard about Liability-Driven Investments (LDIs), or, at least, had not predicted the damage they would cause. Full disclosure: I include myself here. In this sense, it reminds us of some of the things that happened in 2007/2008. We had not predicted it, but it evolved into something really big.

The Bank of England (BoE) intervened. It promised to buy gilts to the tune of GBP 5bn per day for a limited period of time. This stabilized markets, and yields fell somewhat, but only temporarily. After a few days, yields started climbing again. The BoE had to intervene again.

In reality, the BoE has not bought a lot of bonds, probably because it collides with their battle against inflation. So, yields have risen, in spite of their (BoE) promise to intervene, as Figure 2 shows. It is a mess.

An anecdote: ATP

UK pension funds lost money because of leverage and derivatives. Allow me to add a small anecdote here. In Denmark we have a pension fund called ATP (link). It is one of Europe’s largest (AUM close to EUR 130bn at the end of 2021). Almost all Danes are members of ATP. It is a defined-contribution plan but members are guaranteed a nominal return on the larger part of their savings. As nominal yields have been low, ATP, like the UK pension plans, leveraged up the portfolio. A couple of years ago I warned that this was a very risky investment strategy (link). I (together with a colleague of mine, Henrik Ramlau-Hansen) claimed that ATP would suffer large loses when markets turn sour. This turned out to be true. During the first six months of 2022, ATP lost 36% while other Danish pension funds lost 5-15% (link). It is another example that the use of leverage in pension funds can be damaging.

Second event: Credit Suisse

The second event is the Credit Suisse situation. Credit Suisse has had its fair share of scandals, fines, and losses, including those associated with lender Greensill Capital (link) and hedge fund Archegos Capital (link). The bank needs fresh capital. Investors are worried.

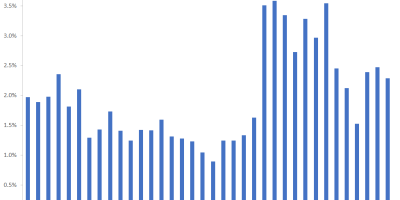

Figure 2 shows the price of Credit Default Swaps (CDS) on Credit Suisse. A CDS insures the buyer of the CDS against losses in case of default of the company against which the CDS is issued.

When the CDS price rises, sellers of protection require a higher price for insuring against default, i.e. sellers of protection view it as increasingly likely that the firm under consideration will face solvency challenges. During recent weeks, the price of protection against a Credit Suisse default has sky rocketed, as Figure 2 shows.

I am not a CDS trader scrutinizing CDS spreads day in and day out. But I did in 2008-2009, when I wanted to know which would be the next bank to be bailed out by some government. Figure 2 reminds me of those black days. Back then, during the financial crisis, CDS premiums for banks that would later fail or receive government support looked like the one for Credit Suisse today.

This is serious business. Credit Suisse in no small bank. According to some rankings Credit Suisse is Europe’s 9. largest bank in terms of total assets (link). No wonder people start talking about a Lehman Brother moment. For sure, if Credit Suisse should enter into a restructuring situation, this would be a threat to financial stability, at the very least in Switzerland.

Third event: The bailout of the energy sector

Since a month or so ago, one European country after the other has rushed to provide liquidity guarantees to energy producers to help them meet margin calls on their hedges. Here is a good overview of the many places this happened and the hundreds of billions involved (link). Why is this important to mention here? Because if the support had not been given, it could had led to defaults of otherwise solvent energy companies, and, hence, lead to significant losses in banks. It would also have disrupted the operations of clearing houses, where derivatives are traded, with negative consequences for financial markets. The relevant authorities argued that, if left unchecked, this had the potential to evolve into a financial crisis. So, for the third time in one month, something we had not seen coming happens. Something so big that it was a threat to financial stability.

Evaluating the events

These three events are all unrelated. The LDI event relates to reckless fiscal policy in the UK and risk-taking in pension funds, the Credit Suisse event relates to losses in that bank, and the energy-sector event to dramatic changes in energy prices in Europe following the war in Ukraine. The noticeable thing is that three events happened within such a short notice of time. And all three events threaten financial stability. What should we make of it?

My current judgement is that I am more concerned about the signal that the UK gilt market event sends than the Credit Suisse and energy market events.

I believe the banking sector is more robust today than, say, prior to the financial crisis of 2008 (I wrote this analysis on the Nordic banking sector, link, but similar conclusions apply to banking sectors in other regions). The financial crisis of 2008 revealed cracks in banking regulation and banking behavior. Regulation has been tightened. Banks are more resilient today. This does not mean individual banks cannot run into trouble. The Credit Suisse event is an example. However, I would be surprised if the Credit Suisse event foretold similar problems in most other European banks. I do not view the Credit Suisse event as a Lehman Brothers event.

Regarding the events in the energy sector, it does not appear to reflect a fundamentally flawed business model. Energy firms had hedged their risks, and extreme price movements caused temporary challenges.

On the other hand, I am concerned that the events in the UK gilt market send a signal that there are cracks in the system, related to bond market liquidity that has, if not disappeared, then at least been significantly reduced after the financial crisis. This could cause further troubles down the road. I will devote my next analysis to this challenge (link).

Conclusion

Prior to the financial crisis, events happened that people at the time thought were idiosyncratic. Later, we understood that they were symptoms of more fundamental underlying risks. These risks materialized during the financial crisis.

Recently, a number of events have threatened financial stability. They all seem to be idiosyncratic. We must hope they are not symptoms of underlying risks.

The event I am most concerned about, and that I view as the most likely candidate for representing a more fundamental risk, is the selling pressure in the gilt market following margin cash calls to UK pension funds.

UK yields rose because the new government ploughed a large hole in the public budget. But they also rose because pension funds sold bonds and liquidity was not sufficient to absorb the bonds. In my next blog post (link) I will analyze the implications of this challenge.