Central banks raise interest rates when inflation is too high. According to textbook models, this should cool down the economy and reduce inflationary pressure. Now central banks have raised interest rates, but labour markets and economic activity have proved remarkably resilient, while inflation has fallen sharply. Perhaps higher interest rates were not necessary to bring inflation down. Perhaps inflation would have disappeared on its own. I doubt it.

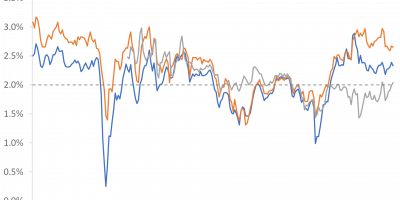

Inflation has fallen as fast as it rose. Inflation in Europe and the US was around 0% in 2020, immediately after the pandemic, rose to around 10% by 2022, and has now almost reached the inflation target of 2% again, as Figure 1 shows.

Source: FRED of St. Louis Fed and J. Rangvid.

One can debate whether core inflation and wage inflation have also fallen sufficiently, but it is a fact that headline inflation has fallen a lot. How is it that inflation has fallen so quickly and so much?

Original Phillips curve

Central banks raise monetary policy interest rates to drive up other interest rates, making it more expensive to service debt. This reduces overall demand in the economy because consumption and investment fall. With less economic activity, labour markets weaken. When people cannot find work, i.e. when unemployment is higher, people hold back their wage demands, which keeps wage inflation low. As a result, companies do not have to raise prices as much. Overall, inflation falls and unemployment rises when central banks raise interest rates, according to the textbook. This is the Phillips curve – a negative relationship between inflation and unemployment – in full force.

Now, during this disinflation episode, interest rates have risen and inflation has fallen, but labour markets are tight and wage inflation is high. The Phillips curve has not worked (link).

This raises an important question: Could we have spared ourselves all the pain of higher interest rates and still seen inflation disappear on its own?

I doubt it.

Expectations-augmented Phillips curve

The original Phillips curve assumes that inflation is low when unemployment is high and vice versa, as described in the previous paragraph.

In the late 1960s/early 1970s, people began to doubt this. Can you really reduce unemployment permanently by simply increasing inflation? It sounds suspicious. The work of Edward Phelps, a professor at Columbia University, was particularly important; so important, in fact, that it earned him the Nobel Prize in 2006 (link). Phelps understood that inflation depends not only on unemployment, but also on people’s inflation expectations. If we all expect high inflation next year, we will demand higher wages today. Companies recognise this and will already raise prices today. Rational expectations are at work: inflation expectations are causing inflation. Thanks to Phelps’ (and Lucas’) work, we no longer use the original Phillips curve in macroeconomic models, but an expectations-augmented Phillips curve, in which inflation is determined by unemployment (or output or the output gap) and inflation expectations.

If you want to know more about the latest research on the Phillips curve, the Economist offers a nice overview (link).

Inflation expectations and inflation

Inflation therefore depends on unemployment and inflation expectations.

While unemployment has remained low during this inflation and subsequent disinflation episode, inflation expectations have also remained low. This is a crucial difference to the last time we had high inflation, in the 1970s.

Today, central bankers know how important it is to anchor inflation expectations. In the 1970s, this was not so well understood. Today, we have inflation targets and focus on bringing inflation back to target when it is too high. In the 1970s, there was a fear that if you try to bring inflation down when it is too high, unemployment will rise (original Phillips curve).

So in the 1970s, inflation expectations rose with the rise in inflation because monetary policy was not tight enough. As we know today, this in itself fuels inflation. Today, monetary policy is tight and inflation expectations have remained anchored.

Let me show you some evidence.

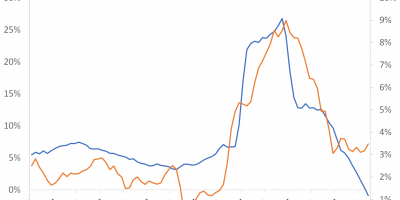

Figure 2 shows that inflation expectations rose just as much or even more than inflation itself during the two inflation waves in the 1970s. Higher inflation expectations fuelled inflation and made it more difficult to bring it down.

Source: Philadelphia Fed and J. Rangvid.

The contrast with today’s inflation episode is striking. Today, inflation has also skyrocketed, to 8% (this is GDP price inflation, see next paragraph). However, inflation expectations have remained anchored, Figure 2 reveals. At their peak at the end of 2022, inflation expectations were 3%, while inflation itself was at the aforementioned 8%. The fact that inflation expectations have remained low even though inflation has shot up is an important reason why inflation has fallen again. Low inflation expectations lead to low inflation, the expectations-augmented Phillips curve says, and this is what we have seen.

Note that I use the – perhaps not so common – GDP price index inflation in Figure 2. The reason is that we have expectations of GDP price inflation going back to the 1970s. Inflation expectations derived from TIPS or consumer surveys, for example, do not go back to the 1970s.

Monetary policy and inflation expectations

OK, so inflation expectations have remained anchored during this inflation episode and have helped bring inflation back down, but have inflation expectations remained anchored because of monetary policy? I believe so. Let me first show you some graphical evidence and then refer to some studies.

Monetary policy got off to a bad start. The Fed (and the ECB and other central banks) raised interest rates too slowly, as I and many others have shouted many times. This can be seen in Figure 3, which shows how the Fed raised the Fed Funds Rate immediately when inflation started to rise in the 1970s, both in the first inflation episode in the early 1970s and in the second in the late 1970s. In 2021, the Fed (and the ECB and others) sat on their hands even as inflation rose rapidly. But, and this is the positive thing, when central banks finally raised rates, they did so in a big way and very quickly. And, probably more importantly, they did not cut rates when inflation started to fall, unlike in the early 1970s: You can see from Figure 3 that as soon as inflation started to fall in the early 1970s, the Fed also lowered the Fed Funds Rate. On the other hand, the Fed did not cut rates in 2023, even though inflation was falling rapidly. I think that inflation expectations would have risen (as they did in the 1970s) if the Fed had not shown a strong commitment to its inflation target.

Source: FRED of St. Louis Fed and J. Rangvid.

Belief is not enough, though. We prefer analyses to substantiate claims. Allianz Research has conducted an interesting study (link). They dissect the 7 percentage point decline in US inflation from Q2 2022 to Q2 2023, finding that tighter monetary policy had a strong impact on disinflation in the US. More specifically, they find:

- Higher interest rates led to tighter monetary conditions, which reduced aggregate demand. This reduced US GDP by 3 percentage points compared to what it would have been without the tightening of monetary policy. Using the Phillips curve (lower output growth => lower inflation), Allianz estimates that this has led to 2% points lower inflation.

- Higher interest rates signalled that the Fed is determined to bring inflation back to target. This has anchored inflation expectations. Had the Fed not raised rates, inflation expectations would have risen, pushing inflation up 3% points compared to where it actually ended up.

- Overall, monetary policy has thus reduced inflation by 5% points from Q2 2022 to 2023.

- In addition, normalisation of supply chains reduced inflation by 5% points.

- Other factors, such as high household consumption due to the high savings and loose fiscal policy (link), have pushed inflation up by 3.7% points compared to the level it would have reached without these factors.

I summarize the findings from the Allianz Research analysis in Figure 4.

Source: Allianz Research (link).

BIS has also analysed the impact of US monetary policy on US inflation (link). BIS concludes that inflation in Q3 2023 would have been more than 6%, instead of the actual 3%, if the Fed had not raised interest rates. Tighter monetary policy has therefore lowered inflation by 3% points, according to BIS.

Supply versus demand

Those who claim that inflation would have disappeared by itself argue that this inflationary episode was entirely supply driven. Disrupted supply chains during the pandemic caused inflation to flare up, and when supply was back to normal, inflation receded.

Supply-chain disruptions certainly played an important role, but strong demand due to strong consumption and expansionary fiscal and monetary policies also contributed, I argue (link).

The San Francisco Fed has developed a decomposition of inflation into supply and demand (and other) factors (link). It is shown in Figure 5.

Data source: San Francisco Fed and J. Rangvid.

Demand-driven inflation has risen by more than 3 percentage points from its low in 2020 to its peak in 2022, as has supply-driven inflation. Supply chain disruptions played an important role, but inflation was not only supply driven. Monetary policy needed to tighten to reduce demand-driven inflation, and it did.

Doing the right thing

Those who claim that inflation rose because supply chains were broken, and fell when they were no more, argue that there was no reason to tighten monetary policy. Inflation would have fallen on its own anyway.

There are even people who argue that “Inflation has come down in spite of the Fed, not because of it” (link). Supporters of this view believe that central banks create inflation when they raise the monetary policy interest rate: When interest rates rise, because monetary policy is tightened, the government must pay more interest on its debt, which is a fiscal stimulus, and, according to this view, this creates inflation.

President Ergodan in Turkey also believed this. He believed that higher interest rates lead to inflation and therefore favoured a loose monetary policy in times of high inflation (link). The result was disastrous. Turkish inflation was 65%(!) in December 2023. Fortunately, policy in Turkey has changed. Turkey is now desperately raising interest rates. It is important to do the right thing.

Conclusion

Inflation is falling, and fast. At the same time, the economy is proving resilient despite tight monetary policy. One might be tempted to argue that there was no reason to raise interest rates to cool the economy in order to lower inflation.

I disagree.

An important task of monetary policy is to influence expectations. By raising the interest rate, the central bank demonstrates its commitment to an inflation target. If central banks had not raised interest rates, inflation expectations would most likely have risen, as they did in the 1970s, making it more difficult to bring inflation down.

Moreover, the economy would probably have been even stronger and inflation even higher if there had been no rate hikes. Ultimately, this was not just a temporary supply-driven event. Central banks had to raise interest rates. Past experiences with alternative monetary policy responses have proved disastrous.